Editor’s note: The following piece was written by the leaders of two Denver charter schools who served on DPS’ Re-Imagine SPF Committee. It’s written as a counterpoint to the piece by Nicholas Martinez published here last month.

By Elisha Roberts and Marcia Fulton

As members of the Reimagine SPF Committee, we worked hard to ensure the community input we received from hundreds of constituents was reflected in our committee’s final report that was supported by a strong majority (84%) of the task force. Last month, another member of the Re-imagine SPF committee, Nicholas Martinez, wrote an op-ed: A commitment to monitoring student progress and equity critiquing recommendations that were presented to the Board of Education.

While we respect Nick’s perspective and the work he does in communities across Denver, we believe he misstates the findings of the committee, and therefore misleads the community about the potential impact of those recommendations. It is our hope to clarify the actual intent of the recommendations and highlight how we all share a common commitment to advancing the cause of equity for Denver Public Schools students.

Martinez appears to offer conflicting critiques of the committee’s recommendation. At one point he argues that by selecting the state’s SPF over its own, DPS is “lowering the bar for school performance.” Later in the article, he seems to suggest just the opposite, that the committee is unwisely relying too heavily on standardized tests, which “favor whiter, wealthier populations over low-income communities of color.”

We feel both of these critiques miss the point of the committee’s recommendation and seem to miss the larger challenge of achieving equity in our schools.

The committee majority’s recommendation was to use the state SPF to serve as the primary vehicle for meeting federally mandated Every Student Succeed Act (ESSA) requirements, thus releasing DPS from this level of federal accountability in order to move into a more holistic approach to school improvement and quality. The State SPF would provide a snapshot of performance as measured by the state assessment (SPF Recommendation 1) and be balanced out by measurements for the whole child and for culturally responsive learning environments (Recommendations 2 and 3).

Information from all of these sources would provide a rich body of evidence that informs the public and could be used to “trigger a local accountability process” if needed. The dashboard, and leveraging a continuous learning cycle, would then provide information and processes to create focused support(s) for schools (Recommendation 2 & 3).

Though Martinez is worried that this move would make it “harder for members of the public to get critical academic data that they rely on to understand what is happening inside our schools,” we feel our recommendations would provide much more information than the public has ever had to truly understand all the ways in which schools provide support to students.

To the question of relying too much on standardized tests, Mr. Martinez’s has a valid point—this is indeed a problem. However, he misstates our proposed solution:

“Many committee members are saying they want more holistic measures of school health, yet they are pushing to adopt a tool that actually places more weight on standardized test scores than the DPS version of the SPF.”

We disagree. We did not adopt the state SPF because we wanted to rely more heavily on standardized tests. The committee felt that the DPS SPF also provided few measures of school health and also relied heavily on standardized test performance.

Numerous school leaders, ourselves included, kept that at the forefront of discussions and is why our recommendation is to use the state SPF plus additional whole child, culture and climate measures. To claim that the committee recommends the state SPF as THE tool is disingenuous and misrepresents the intent of the committee’s recommendation in its entirety.

Numerous members of the committee shared painful experiences with the DPS SPF and how it negatively impacted the morale of administrators, teachers, and students who worked SO HARD year over year to overcome societal inequities without the resources needed to really make an impact. The goal of the combined recommendations is to highlight where schools are today—the outputs—and where more support could be given to ensure they succeed—the inputs.

Martinez writes:

“At a time of national crisis, where we are more acutely aware than ever of privilege, the majority-white committee is eliminating the accountability tool that measures whether all students are getting access to an equitable education.”

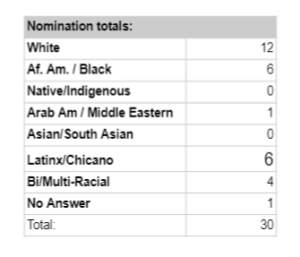

We agree, now more than ever, that access to a high-quality education for the underserved, predominantly low income and minority communities, remains critical to ensure and secure the future success of our students. We take issue with the idea that a majority-white committee eliminated this opportunity for our families. The people of color on the SPF committee represented teachers, administrators and parents and are shown in the “Nomination totals” table. Over-simplifying that the majority were white misrepresents the voices in the room.

Martinez explains:

“This, in turn, favors whiter, wealthier populations over low-income communities of color. Additionally, a move to the state system would make it harder both to identify places of innovation and success whose wisdom should be shared and would leave entire communities underserved without identifying much needed areas of intervention that highlight opportunities to create change.”

Because of the nature of high-stakes testing, and how the data is used, we agree that the state SPF favors whiter, wealthier populations over low-income communities of color. In order to expect different results, regardless of the measurement tool, there must be different inputs.

The current version of the DPS SPF also highlights already known inequities in our system. We rank and cluster schools. This does not foster innovation and the sharing of wisdom, but most often simply highlights a school’s context. It means schools hope for others to underperform so they can show a higher ranking or perform better in their cluster.

Through our color-coded rating system, we have decided what parents should value and at what weight, instead of allowing them to look at a body of evidence and bring their set of values to the data and make informed decisions. A true learning system, like the one we recommend, leverages a body of evidence that identifies much needed areas of intervention, strengths, and would create opportunities for change.

And finally, Martinez states:

“Making this move from the Denver SPF to the Colorado SPF will ensure that when school resumes after the coronavirus interruption, we won’t know where we stand. We won’t know how many of our students have thrived while being at home learning with their families, which means that we won’t be able to learn how to create that healthy learning environment for others.”

In both SPF systems, the role of high stakes assessment is the driver. To say that schools will not know where they stand without these accountability systems/assessments is simply false. Every day, teachers assess the learning of their students and know their strengths and areas of growth. Teachers and school leaders are in communication with families and know which students are thriving and which are not — no matter the learning environment.

In most cases high stakes assessments, and therefore the current SPF models, tell schools what they already know. It is a more robust body of evidence across a set of values represented in our second and third recommendations that will produce the learning environments in which students thrive.

We agree with Martinez that equity must be the goal, and that we should neither lower the bar nor rely on methods that appeal to one population but not all. Our committee has proposed what we believe is the proper remedy—that we use the state SPF as a consistent standard that applies to all schools (Recommendation 1) while acknowledging the unique circumstances each school faces in serving its students well (Recommendations 2 & 3).

A way to foster equity is to enact policies that allow for everyone to live up to their full potential, while acknowledging we all have unique needs to get there. As the graphic depicts, one size does not fit all, but we can ensure that everyone has what they need to succeed. The current cries for equal humanity in our country clearly demonstrate how far we have to go to close the equity gap.

We have not achieved equality in our communities nor in our district, so the conversation around equity is that much harder to achieve. We all do not begin from the same starting point, therefore a one size fits all approach to accountability metrics misrepresents the context in which our communities live.

People argue about how to measure outcomes while never discussing what conditions would need to exist within our schools to achieve those outcomes. We tend to focus our attention on how to measure what we are already doing, instead of determining different inputs and measurements needed to close opportunity gaps creating more equitable outcomes in our schools.

We must be asking the questions: What will it take to actually reach equality in our society? What will it take to reach true equity in our schools? What keeps us from taking actions to make equity a reality?

Elisha Roberts is a Principal at STRIVE Prep – RISE, and Managing Director at STRIVE Prep. She has a bachelor’s degree from Occidental College and a Masters of Education, Curriculum and Instruction from Boston College. In 2016, she founded STRIVE Prep – RISE, a new high school model for the network built on a social justice focus, a restorative culture system, and an unapologetically college-going culture. Elisha was born and raised in Denver, and spent time living and learning abroad in Botswana, Papua New Guinea, Japan, and other parts of Southeast Asia and Europe. She has a daughter and fiance whom she treasures.

Elisha Roberts is a Principal at STRIVE Prep – RISE, and Managing Director at STRIVE Prep. She has a bachelor’s degree from Occidental College and a Masters of Education, Curriculum and Instruction from Boston College. In 2016, she founded STRIVE Prep – RISE, a new high school model for the network built on a social justice focus, a restorative culture system, and an unapologetically college-going culture. Elisha was born and raised in Denver, and spent time living and learning abroad in Botswana, Papua New Guinea, Japan, and other parts of Southeast Asia and Europe. She has a daughter and fiance whom she treasures.

Marcia Fulton has worked in education for 28 years as teacher, instructional coach, director of curriculum and instruction, and as the Executive Director of two Charter schools in Denver. She believes in the power of the collective working together to educate our youth. In this environment, students are taught how to be agents of their learning. She would describe herself as one who leads with her heart and with her mind. Marcia believes that teaching and learning is a human endeavor. In her own words, “it is when we know and trust each other that relationships are formed, and learning can happen. It is through intentional decisions about how we experience learning that we engage and become inspired to be all that we can be.”