Updated: This post has been updated to point out that state law mandates that pencil and paper tests must be provided by the state at an “education provider’s” request.

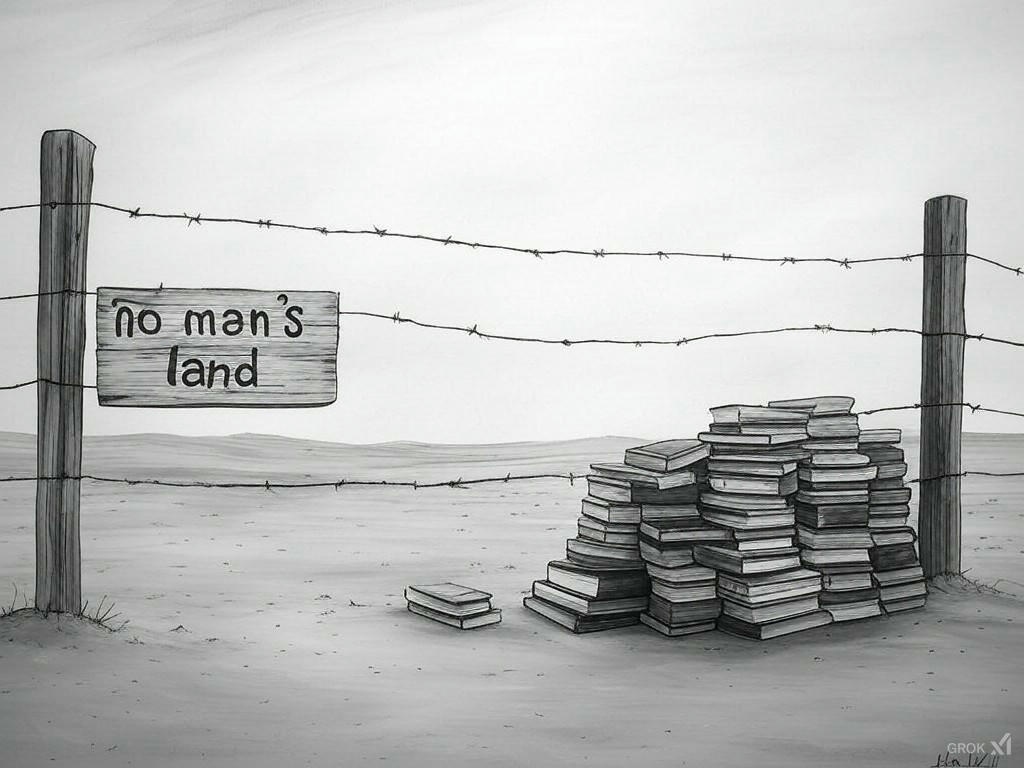

Whether to conduct state testing in Colorado this spring has become the latest issue over which two polarized sides are preparing to engage in pitched battle.

As is true with most education issues, nuance and context matter. This isn’t as simple as some people on either side of the issue would lead one to believe.

My initial inclination was to come down hard on the side favoring some testing this spring. Then I talked to a veteran metro-area educator I know who coordinates testing at her school. The conversation gave me an appreciation for the immense logistical hurdles schools face in making this work.

I still favor doing a small amount of testing, but only if the state can figure out how to overcome practical challenges caused by the pandemic.

There are multiple compelling arguments for conducting testing. We have all read about how much learning loss students have suffered since the Covid-19 pandemic first closed schools almost a year ago. We’ve heard how those losses have disproportionately hurt the kids who can least afford them.

Shouldn’t we want and need to quantify those losses, so we can begin to build strategies for mitigating or overcoming the widening gaps they will cause? Of course we should; especially since the state canceled testing last spring. Two years is a long time to go without data, as flawed as it might be.

Wouldn’t it make sense to decouple teacher and school accountability from the tests this year, so that no one need worry about being sanctioned for circumstances beyond their control? Of course it would. Few if any proponents of testing are arguing otherwise.

Couldn’t we figure out a way to scale back the bloated testing regimen so that students don’t suffer more learning loss by spending a week or more taking tests that do nothing to advance their education? Yes, we could. And should.

Those are the arguments that had persuaded me. A poll released this week by Ready Colorado, Democrats for Education Reform, and Colorado Succeeds, conducted by the reputable Keating Research firm, found that Coloradans, by a substantial 62%-25% margin, support administering tests this year, as long as they are not tied to teacher or school evaluations — purely for informational purposes.

But now let’s look at reality, through the eyes of someone who is actually living through this situation. Let’s call her Mary. I am protecting her identity because she is not authorized to speak for her school or her district. Knowing I’d mask her identity, she was willing to speak with candor.

At Mary’s school of several hundred students, about one-third of all students were given laptops to take home this year. Her school has one day of remote instruction per week, and cohorts of kids attend in person for two full days each week.

If testing occurs, Mary and her team will have to collect those several hundred laptops from students and bring them back to the school.

Why? Because testing has to occur at school, not home, and the school doesn’t have enough computers at the school to conduct testing. This means those students will not be able to attend the one day of online school each week, exacerbating learning loss. And since the kids who needed computers from the school district are disproportionately low-income, taking their computers will also widen learning gaps.

“It’s not equitable or fair for us to say ‘we’re still going to have class but you can’t attend, because we had to take your computer for testing,’” Mary said.

Mary will have to take each computer retrieved from a kid and check to be sure the operating system has been updated by the student, so that it can run the Pearson Education software that powers the state test — Colorado Measures of Academic Success. It’s likely that many of the computers will have to be updated. Mary has six electrical outlets in her classroom, so you get an idea of how long this will take.

This is one school out of thousands. Multiply the complexities and you gain an appreciation for the logistical nightmare testing poses this year.

Update: What Mary might not know is that state law requires the Colorado Department of Education to provide paper-and-pencil tests if any “education provider” requests them instead of computer-based tests. This means that the collecting of computers from students is, by law, unnecessary. But given the uneven quality of communications between CDE and districts, and from district offices to schools, staff on the ground in schools could well be unaware of this.

To date, Mary and her peers have received little information about what the state will do this year. Most educators, she said, are operating under the assumption that testing will be cancelled. But Governor Jared Polis has come out in favor of testing, and so far, no decision to eliminate or reduce testing has been made. What’s more, it all may have to be done under a compressed timeline.

Finally, Mary raised a valid question about the utility of testing this year. Most if not all schools are doing internal diagnostic testing, so educators have a good idea how their students are doing. What, in the end, is the purpose of the state test this year?

I’d argue that the purpose is to give policymakers and the public information about how pandemic learning loss has been distributed across the state, and more importantly, across subgroups of kids. This information should help inform decisions about how to enact policies and distribute funding to mitigate those losses and close widening gaps.

Mary acknowledged that those could be useful outcomes. But she was skeptical. “The results are not going to surprise anyone, and that is where a lot of teachers are coming from,” she said. “What do they expect to find? Yep, the kids didn’t learn much of anything. We know it’s going to be bad. We know kids have lost ground, without even looking at test data. So why put everyone through this?”

Those are reasonable questions. At the end of the day, I’d urge the state to find ways to pare testing down to the bare minimum, and help districts find ways to overcome logistical hurdles. Perhaps there are also ways to push the testing window out to May, and to give tests the old-fashioned way: using pencil and paper.

If that’s not possible, perhaps testing this year is much trouble for little useful data.