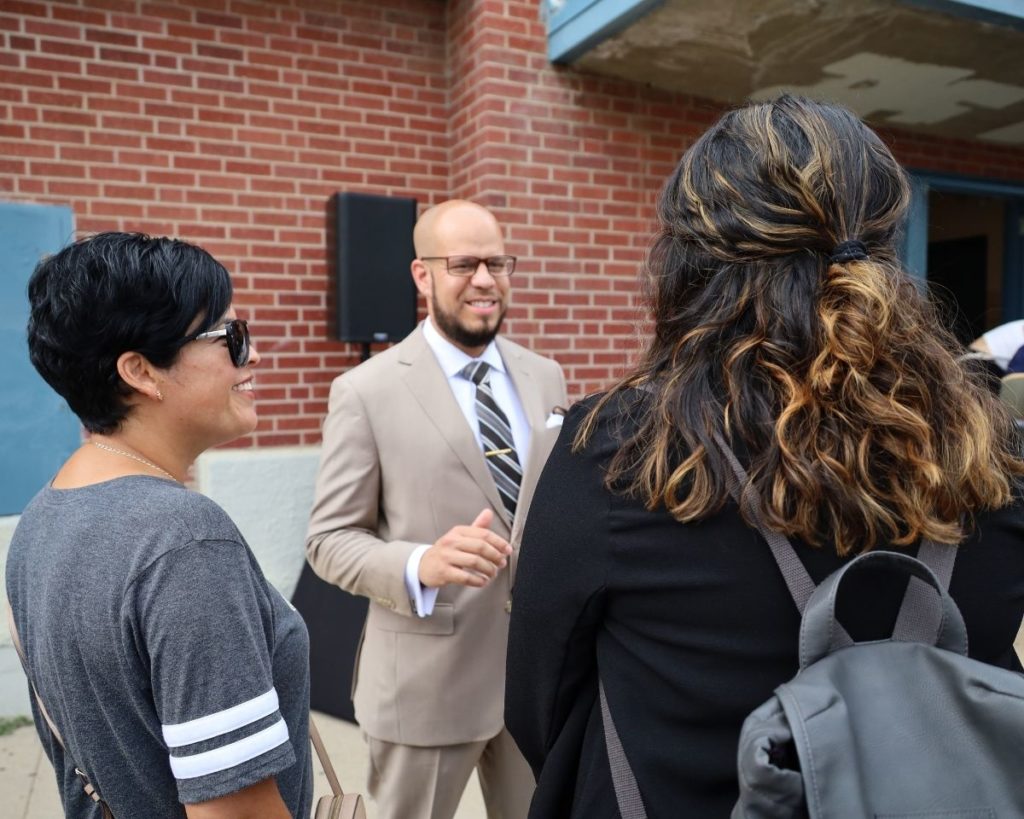

Alex Marrero has been on what he calls a “listening and learning tour” since becoming superintendent of Denver Public Schools in July. Now he’s facing his first tough challenge, and will have to use all of his political and interpersonal skills to craft a solution.

The issue? School safety after the removal of School Resource Officers (SROs) from 18 middle and high schools at the beginning of this school year.

From the beginning of school in late August through the end of September, DPS, (like school systems around the country) has experienced a significant spike in violence and drug violations in and around its schools.

According to an email Marrero sent to the advocacy group Padres y Jovenes Unidos September 27, “we have already confiscated four loaded firearms on school campuses, multiple weapons (including a machete), weapons such as guns, tasers, etc., and experienced one student stabbed with a knife.”

Overall, there has been an “almost 25 percent increase” in high priority calls from schools for assistance from DPS’s internal security team compared to the same period in 2019, Marrero wrote. This includes a 5 percent percent increase in assaults, and a 21 percent increase in fights.

No one is suggesting that the spike in incidents is related to the absence of SROs. In all likelihood, it’s related to tensions that built up among youths outside of school during the pandemic, one school leader said.

“Think about kids who have been handling issues on their own, in their neighborhoods, and mostly haven’t been in school for a year and a half. Now we’re going to come back into school and just expect kids to go with the flow and not address some things that have accumulated over that time?” said the school leader, who asked not to be named.

The absence of SROs means the district must rely either on its internal security force or on calling the general police number for response, without the intermediary influence of the SRO, who used to provide responding officers with important context to prevent escalation.

Is this a sustainable situation? Or does the district need to find some middle ground between having no Denver Police Department presence and addressing the concerns of school leaders, who have a close-up view of the reality on the ground? That’s the needle Marrero will need to thread. No decision will make everyone happy.

Data suggest something needs to happen, and the sooner the better. According to information provided by DPS from a Colorado Open Records Act request, district schools experienced the following between the start of school and the end of September:

- 62 assaults

- 102 student fights

- 11 sexual assaults

- 29 weapons violations

- 8 assaults on staff

- 8 narcotics violations

- 48 marijuana violations

- 65 ‘threats’

- 73 ‘unwanted individuals’ on school grounds

In a virtual meeting with Padres y Jovenes Unidos in late September, Marrero said the security situation alarms him. “We have had major, major incidents that have me a little bit nervous,” Marrero said. “These are well beyond a dispute at the eighth grade or fifth grade level. These are things that make my ears go up, drop what I’m doing and head on over (to a school). When it comes to firearms that are loaded, and students who just engaged in an altercation. It is my number one priority to make sure that there’s nothing that will happen that means we will have to be devastated for years to come.”

In the immediate aftermath of George Floyd’s murder last year, the DPS board voted unanimously to remove resource officers — sworn members of the Denver Police Department — from its schools. Board members said the presence of armed officers in schools was traumatizing for students of color, and particularly Black students, who so often are singled out and treated harshly by cops on the streets.

Board members also said, with backing by groups like Padres, that having cops in schools represented the entry point for the notorious school-to-prison pipeline.

From the beginning, however, principals in the schools that hosted officers objected to the decision. They argued that most of the officers were people of color, who had worked in the schools for years and had established strong relationships with students.

They also said that the resource officers understood the dynamics among students in their schools, knew how to defuse situations, and, on the occasions when they needed to call for back-up, got a quick response and were able to give the responding officers context to keep situations from escalating.

At a school board public hearing on the issue on June 11, 2020, North High School Principal Scott Wolf had this to say about the pending removal:

“There is a lot of evidence from our school sites in Denver that have SROs that they are an incredible asset, and eliminating (them) is solutions-focused instead of root cause-focused…I do not think anyone except those of us who work with SROs understand what (they do) on a daily basis and how they serve as peace officers.”

I reached out to several school leaders and they were unwilling to speak on the record about this fraught issue. The exception was Eric Rowe, principal at PREP, a middle and high school serving students that have struggled in more traditional schools. Although many PREP students have been involved with the criminal justice system, PREP has never had an SRO on its campus.

Rowe, who also serves as co-president of the Denver School Leaders Association, the new principals union, said the debate over SROs misses the larger issue that needs addressing.

“I think the idea of what we think of as safety hasn’t really been fleshed out and considered,” Rowe said, emphasizing that he was speaking for himself and not the DSLA. “We haven’t had what I would consider a community-wide conversation about that. Thank God, knock on wood, we haven’t had a shooting in school. But we have had numerous shootings in community. And what no one really wants to talk about is the why.”

Rowe also said the removal of SROs has no bearing on “the violence and the crime that is happening largely among male students in community.”

It’s a fair point. Meanwhile, though, Marrero seems to recognize that something needs to change, and soon — before something awful occurs.