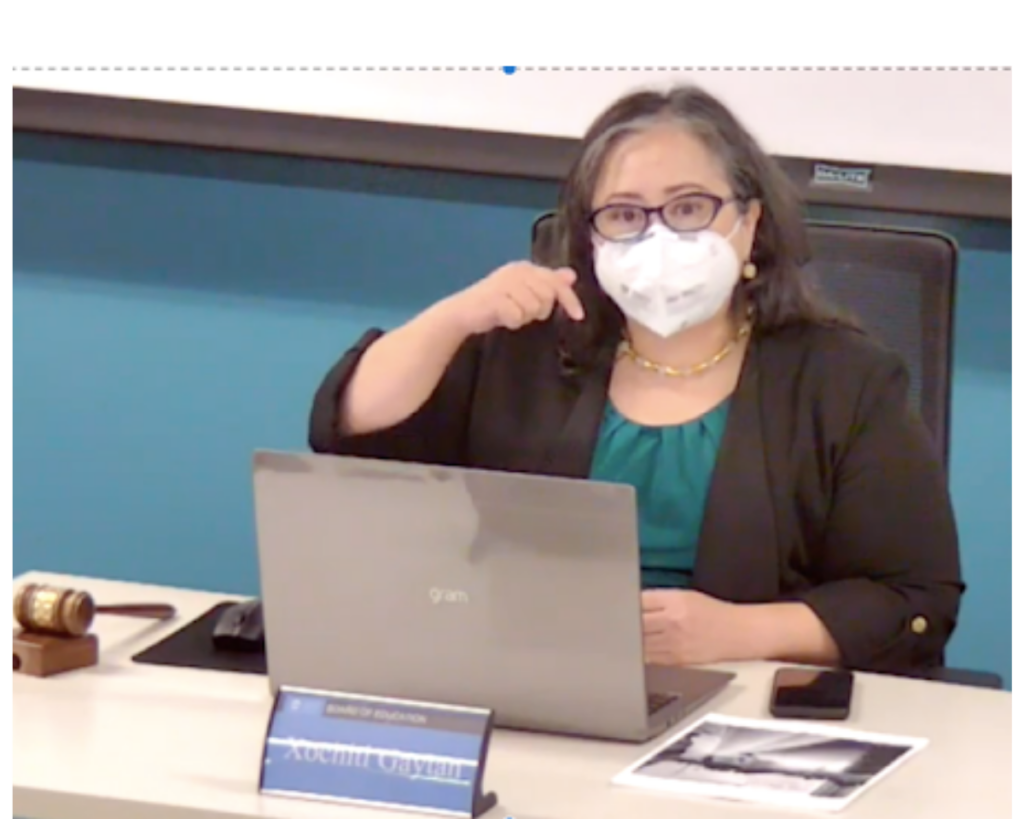

The Denver Public Schools board voted 6-1 Thursday to approve 16 charter schools’ contract renewals. Board President Xóchitl “Sochi” Gaytán cast the only dissenting vote.

Even some of the yes votes were accompanied by ambivalence, but board members said they wanted to respect the wishes of Superintendent Alex Marrero, and to acknowledge that charter school leaders had come to the table in good faith.

When DPS staff provided Marrero with recommendations for the 17 charter schools up for renewal, they had recommended that all but one continue operating for at least two years.

The board voted to renew the other 16 on Thursday, but with some conditions.

The board’s hesitancy to renew charters stems from some members’ stated belief that charter schools exacerbate the declining enrollment problem in traditional DPS schools. They voted yes on the renewal contracts, but on a condition that charter schools stay open to discussing the district’s “small schools resolution,” which could result in closures of schools with low enrollment.

“I started my tenure on the DPS board with a lot of fear, reservations, frustrations and anger about charter schools,” said Carrie Olson, who’s in her fifth year as a board member. “It’s still painful for me and many others about the way in which the closure of district public schools has fueled the growth of charter schools across Denver.”

Saying a third of the charter schools up for renewal are in her region of Southwest Denver, Gaytán also repeated the incorrect assertion that district-run schools are losing students to charter schools.

Gaytán, who was elected in November, said previous board members had allowed charter schools to “siphon” students away from district-run schools.

But according to district data, declining enrollment in DPS is not caused by charter school attendance.

Over the last decade, Denver has seen significant social changes contribute to a declining school population: lower birth rates, less affordable housing, families moving out of the city and childless adults moving into it, to name several.

Families of charter school students select those schools through the same “SchoolChoice” program that families of district-run school students participate in. While those students may not have chosen to attend their traditional neighborhood school, this was a decision they and their families made on their own.

Additionally, students who leave district-run schools are more often than not choosing to attend a different district-run school. Out of 51,000 Denver students attending a school other than the one for which they’re zoned (called “boundary schools”), 33,000 of them still attend a district-run school while 18,000 attend charter schools.

A different concern, expressed in a blog post by board Vice President Tay Anderson, was that Denver charter schools were engaging in a “pressure” campaign for the board to approve the charter schools’ renewal contracts. He wrote, incorrectly, that such a campaign might be illegal.

Social media saw an increase in posts favoring the charter school renewals — including the Denver School of Science and Technology, a charter school network, tweeting the hashtag #HonorRenewals and tagging board members — and Anderson said it was part of a campaign to pressure the board into making a decision based on political leanings instead of actual evidence.

“I believe that this coordinated effort to pressure the Denver School Board could be a violation of state law,” Anderson wrote in his post.

Alex Medler, director of the Colorado Association of Charter School Authorizers, said he understands how a social media campaign could cause frustration, but there’s nothing illegal about it.

“It is inappropriate to suggest that people participating in the community input processes related to charter applications or renewals are violating state law or the Colorado authorizer standards,” Medler said. “While organizing by people supporting charters or opposing charters may increase the amount of input, and create political pressures, best practices in authorizing include ways to manage and incorporate input.”

It would be cause for concern, for instance, if the board ignored evidence that charter schools were failing students in some way and approved their renewal contracts anyway because of community pressure. But that is not the case here, Medler said.

“The rule isn’t even about law, it’s about how the state board will interpret something during an appeal,” Medler said. “In no case would the people giving the input be breaking the law. The issue would be if the board listened to them and then overruled all their evidence to respond to a political campaign.”

Medler also said he understood that some board members might be “frustrated by someone else’s campaign effort, but I thought the testimony the parents and students and teachers gave was all pretty solid,” Medler said about the vote.

“I thought it all worked out better than people were afraid of.”

Another reason some board members said they voted yes on the charter renewals despite their own reservations is that under their newly adopted policy governance framework, contract negotiations are the responsibility of the superintendent and his staff. To keep up a united front with Marrero (for whom a contract extension was also recently approved) the board validated the superintendent’s recommendations instead of combating them.

“I cannot say that I believe in the leadership of Dr. Marrero and then discount his recommendations,” said Michelle Quattlebaum, the DPS board member representing Northeast Denver.

If the board is asking the community for its trust, Quattlebaum said, then it’s important for them to show that they have their own trust in Marrero’s decision-making.

Although the DPS portfolio team had given Marrero their analysis and recommendations last month, the board was clear that the recommendations they considered on Thursday came directly from Marrero himself.