At a Denver school board work session a couple of weeks ago, staff presented some deeply troubling data showing how far behind elementary school students have fallen in both math and reading over the course of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The numbers were jaw-dropping: 76 percent of students in grade 3-8 are below grade level in reading, according to, in edu-speak, interim assessments given in the fall. Some 60 percent of students in grades 3-8 were lagging in math.

Perhaps more disturbing, 28 percent of students in kindergarten through third grades scored significantly below grade level in early literacy. And assessment results in math and literacy are even worse for ‘focus groups’ – students with disabilities, Black/African American students, Latino students, and multilingual learners.

Tamara Acevedo, Denver Public Schools’ deputy superintendent of operations presented these numbers in straight-forward, unadorned language. She wasn’t sugar-coating anything, nor was she pumping up the alarm.

Watching and listening online, I was stunned at the magnitude of the challenge DPS faces in catching these students up and giving them a chance to graduate from high school prepared for life.

Equally disheartening was the thundering silence with which this news was met by the school board. President Xóchitl “Sochi” Gaytán asked a question about why charter school data wasn’t included. Board member Michelle Quattlebaum asked for more information about the performance of Black students and students with disabilities.

But that’s where the questions ended. Since this new board took office in late November, meetings have been run strictly by the clock, and when time arbitrarily runs out, there is no room left for questions even on an issue as fundamental to the board’s job as whether students are learning. And yet no one pushed back on this or asked additional questions.

Late last week, the advocacy group Transform Education Now (TEN) began posting the data on social media, asking “how is this not an emergency?”

To his credit, school board Vice President Tay Anderson responded, expressing a needed and heretofore lacking sense of urgency.

“I am deeply concerned with the recent data regarding our reading scores in Denver Public Schools,” he tweeted. “Our attention as a School Board are (sic) on items that can be placed on pause while we focus all of our attention on the 76% of DPS students not reading on grade level. I’m willing to work with anyone to find solutions on how we address this gap. The Board of Education should be focused on our students, if we can’t meet this moment we will fail them, again.”

Anderson is spot on, even if the focus of his board work has also at times strayed from the core mission of student learning. This board has been focused on non-existent crises like teacher rights in innovation schools while the district’s proverbial house is ablaze. I hope TEN’s social media campaign and Anderson’s response galvanizes the board to turn away from needless, performative distractions and start doing its job.

But there’s another issue intertwined here: The board and its supporters’ hostility toward annual standardized state testing. As Acevedo pointed out during her presentation, the interim assessments from which the data was extracted do not correlate with the state CMAS tests. After a partial pause over the past two years, testing is resuming this spring.

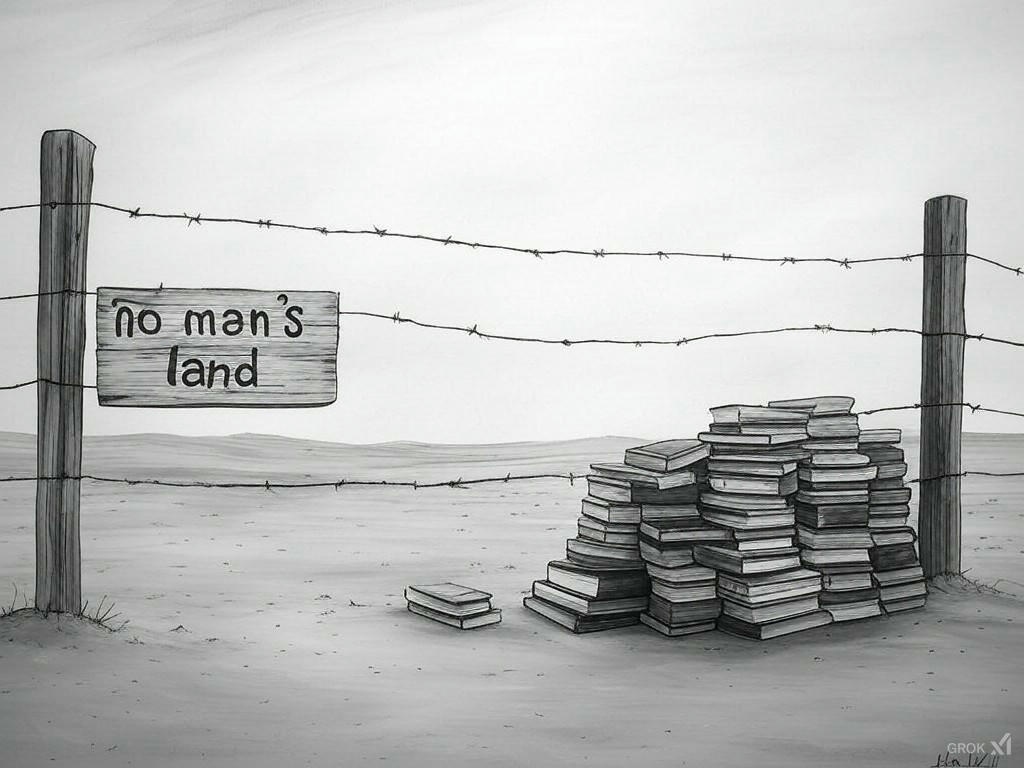

In the recent past, some Denver board members, Anderson among them, actively and vocally encouraged families to opt their children out of the CMAS testing. There is no doubt that over the past decade, testing became excessive, and needs to be cut back significantly. There’s also the real issue of cultural biases baked into the test in ways that can skew results.

Despite these legitimate concerns, widespread state testing is more urgently necessary now than ever before. As Voltaire said,, do not let the perfect be the enemy of the good – or even the adequate.

There needs to be a standardized way to measure just how profoundly pandemic-related learning losses have hit Denver’s students, and whether Denver has done a better or worse job than neighboring districts in addressing these losses. There are real lessons to be learned that should inform strategies moving forward.

Under current circumstances, to urge parents once again to opt out of testing would be the worst form of educational malpractice. Let’s hope common sense prevails over ideology.