While the Denver school board was busy late last month focusing on adult-centered concerns like stripping the district’s innovation schools of future flexibility, an advocacy group received some detailed data showing just how dire Denver’s academic emergency has grown.

Transform Education Now (TEN) filed a Colorado Open Records Act request and the resulting data provides a deep dive into how profoundly Denver Public Schools students are struggling in reading and math in the wake of the Covid pandemic.

The numbers are bad across the board, and deeply alarming when you disaggregate them by race and ethnicity. This disaggregated data, which is public information, wasn’t released until TEN requested it. Little wonder: it shows that whole cohorts of kids are struggling mightily and those are the very same kids who can least afford to fall farther behind their peers and state standards.

The data came with some caveats from district officials. Not all students at any grade level were tested. Some 58 percent of third-graders were tested in “English Language Arts” and 54 percent in math. (If I were a district or building administrator viewing these numbers, I’d demand that all kids get tested post-haste.)

Interim assessments, officials wrote,“are not comprehensive and should be considered a ‘dipstick’ measurement rather than a full picture of how a student is currently performing on all grade level standards.”

And: “District-created interim assessments are not designed to measure student growth from one assessment to the next, nor are they designed to be predictive of student performance on (state standardized tests), but rather assess a student’s mastery of grade-level content at that point in the school year.”

The two paragraphs above offer the perfect argument for why some state-mandated tests remain essential, despite the efforts of many, including current DPS board members, to eliminate them.

Since taking office in late November, the DPS board has largely ignored how DPS is performing its core function: educating students. Some board members – Tay Anderson, Michelle Quattlebaum, and Carrie Olson – have begun saying that it’s time to pivot away from adult priorities and back to kids, the district’s core constituency.

Some others, most notably board President Xóchitl “Sochi” Gaytán, have shown little outward interest in how kids are doing academically. “…part of what I believe is the vision for this board (is) to continue to move forward so that we are affecting our teachers in a positive way,” she said during the recent innovation schools debate, never once mentioning students or academics.

That’s problematic, given that the data reveals that in several schools in the part of town she represents, 0% of tested third-grade students – that’s not a typo – were meeting or exceeding grade level in reading.

I’ve had a chance to review the data TEN received, and I have five questions to which the board might demand answers from Superintendent Alex Marrero and his academics team.

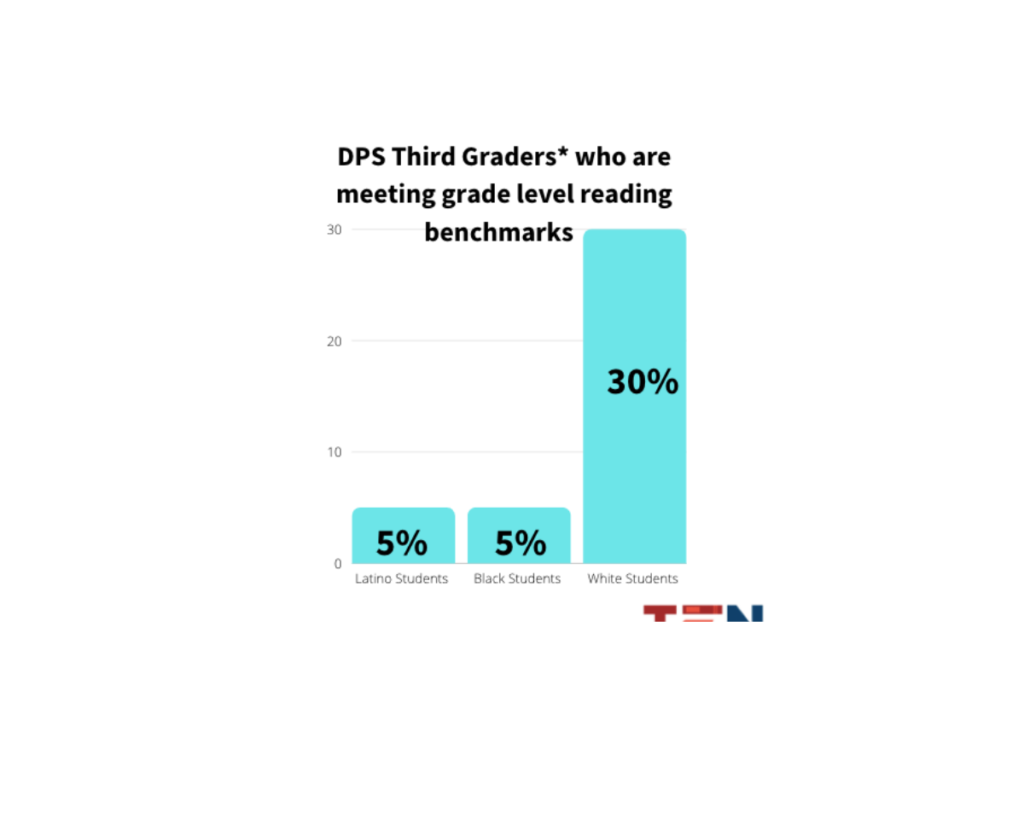

- Reading at grade level by the end of third grade is considered predictive of future academic success. Yet according to the data, just 5 percent of Black third-graders and 5 percent of Latino third-graders met or exceeded grade level in assessments given last fall. Given the emphasis placed on equity, how can the district explain this, and what, specifically, is being done to address this dire emergency?

- Similar to question one, no sub-group of third-grade students has more than 30 percent meeting or exceeding grade level (white kids are at 30 percent). How is the district planning to catch its students up so that an entire age group isn’t facing insurmountable hurdles as they progress through their academic careers?

- While older students, who had more pre-pandemic schooling, are doing marginally better, the numbers are still dismal at best. The strongest results are in eighth grade, yet even there just 24 percent of Black students and 25 percent of Latino students met or exceeded grade level in reading. Given that three out of four Black and Latino students struggle with reading on the cusp of high school, what strategies is the district putting in place to avoid a massive kids of color dropout wave in the coming years?

- Even as the school board moved to rein in innovation schools, four times as many Black and Latino third-grade students in the Northeast Denver Innovation Zone are meeting or exceeding grade level in reading than in the district as a whole. (The numbers of students in subgroups other innovation zones were too small to be reported publicly). Given this fact, what is the district doing to learn from those schools and to make sure the board’s misguided policy change doesn’t reverse these trends?

- If this hasn’t gotten board members’ and district leadership’s attention, what will?

Perhaps a month or six weeks of mandatory summer school for all struggling students, paid for with federal Covid relief dollars, would be a small first step in the right direction. But since adults wouldn’t like that, it’s not going to happen.

It probably won’t even get discussed.