UPDATED below with Auon’tai Anderson accusing the board president of ‘anti-blackness.’

Monday’s Denver school board meeting offered an almost perfect microcosm of the board’s operational ineptitude over the past 16 months: struggling to get out of its own way, and then making terrible decisions when it finally does.

Two issues dominated the proceedings. First was board President Xóchitl Gaytán’s effort to rebuke and perhaps censure Vice President Auon’tai Anderson, which was unceremoniously slapped down by her six colleagues as ill-timed in the extreme.

The second was the board’s decision to endorse Superintendent Alex Marrero’s power grab by voting to dismantle the Beacon Network Innovation Zone. Marrero assured the board that under his steady hand, student learning issues at Kepner Beacon Middle School would be corrected rapidly.

In falling for that line, the five board members who voted to terminate the zone earned an F in recent Denver Public Schools history. Kudos to Anderson and Carrie Olson for voting no.

Gaytán decided to go after Anderson for upstaging her and the rest of the board by holding press conferences and appearing on TV news programs in the wake of the March 22 shootings of two East High School deans by a student who later committed suicide.

She asserted that Anderson violated board policy by going rogue, making intemperate and false statements, and violating the confidentiality of a (likely illegal) executive session.

Taken on its merits alone, Gaytán’s grievance against Anderson is valid. He has himself admitted that his large ego can cause problems. ““[P]ut me in front of all the cameras. Let all the cameras be on me. I’m the center of attention. I take accountability for that . . . that’s me,” he told investigators in 2021, the last time he faced censure.

Having chaired and served on multiple nonprofit boards over the years, I know what a headache it can be to deal with a board member who won’t or can’t be a team player. I get Gaytán’s frustration.

But how tone-deaf, or perhaps ego-driven, does she have to be to think this particular moment is the right one to go after Anderson for what are basically trivial offenses? Apparently Gaytán cannot abide having her authority and title usurped.

To their credit, her board colleagues were having none of it, less than three weeks after the East shootings, with the community still reeling and roiled. Board member Michelle Quattlebaum summed it up nicely:

“I ask us as a board that we ensure that we are honoring the lives that have been lost, that we do not engage in conversations and activities that derail us from this pressing issue before us, that we stay focused and we stay centered on what really matters,” she said. “That should be our number one focus. Something that’s happening amongst us is not even secondary. It shouldn’t make the top 10. It doesn’t matter at all.”

It seems certain that the ongoing power struggle between Gaytán and Anderson is not over. But it has been put on the back burner for now.

[UPDATE: Oops! I spoke too soon. Early Tuesday, Anderson released a statement “from the office of the vice president” accusing Gaytán of “anti-blackness” for moving to censure him. “This attempt to silence my voice is reminiscent of the recent events in Tennessee, where two Black lawmakers were expelled from the Tennessee House of Representatives for speaking up and holding those in power accountable,” Anderson wrote. So while saying it is time to focus on important issues, Anderson is ensuring that his power struggle with Gaytán remains front and center.]

Unfortunately, with that distraction set aside, the board was able to set its sights on the Beacon innovation zone. Marrero and his team made two arguments for ending the zone, one based on governance, the other on performance.

Marrero’s problem with the zone’s governance is that Alex Magaña, a proven DPS school leader over more than two decades, runs the network, reporting to its independent, nonprofit board, but remains an employee of the school district. DPS wants Magaña either to resign from DPS and become a zone employee, or dissolve the zone and continue working for DPS. They don’t like paying someone who doesn’t report to them.

While Magaña and his board rejected governance changes, surely this could have been worked out in negotiations. After all, 100 percent of the Kepner and Grant staff supported the schools’ innovation plans.

On performance, Marrero and Co. used data disingenuously to portray Kepner Beacon as a failing school. In fact, when Kepner was last under direct district control, students performed worse the longer they remained in the school, a trend that reversed under Magaña’s leadership.

Last school year’s Kepner test results were dismal. But when has one year of poor performance caused DPS to upend a school? Never. Until now. Marrero insists that the Beacon schools will be the same, only better, under district guidance. That’s dubious at best.

I know Magaña and the Beacon Network well. In 2016 and 2017 I wrote two case studies about the creation of the Beacon Network for the Rose Community Foundation. I embedded myself in the schools and spent a great deal of time with Magaña. I therefore find it laughable when Marrero insists that once the schools are back under the district’s suffocating wing, the Beacon schools will get all the help they need.

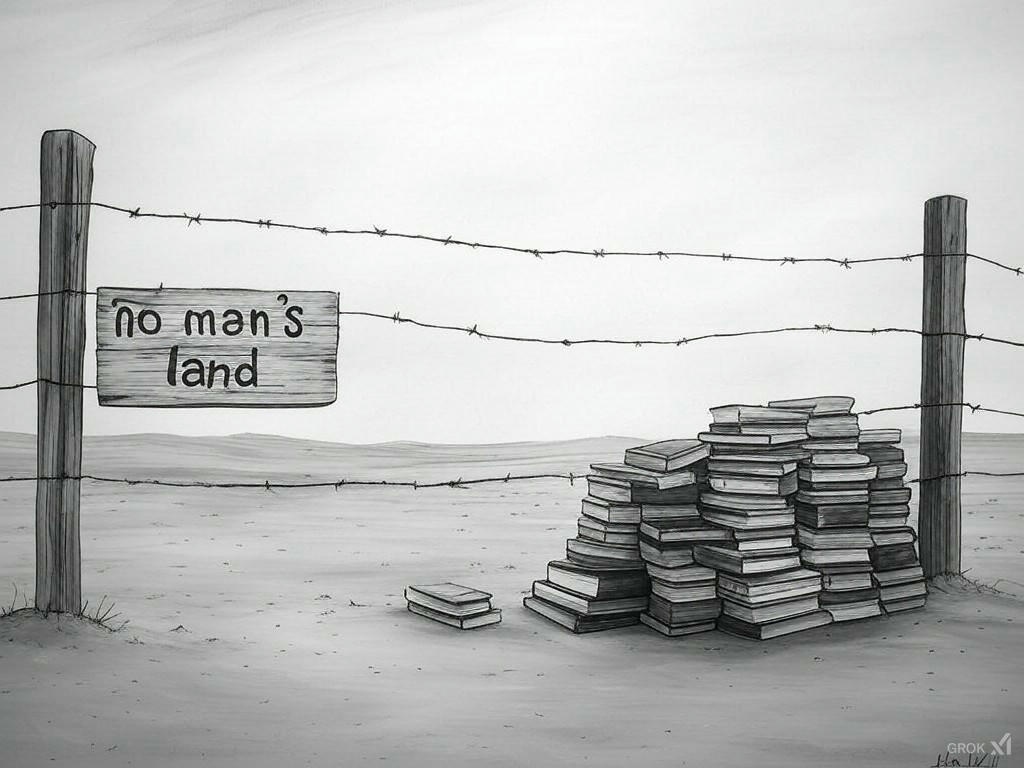

The truth is that under DPS, Magaña had to fight tooth and nail to extricate himself from useless principal meetings downtown and reams of meaningless paperwork so that he could spend time doing what principals are supposed to do: leading a staff and running a school.

More likely than not, the board’s decision Monday night will hurtle Grant Beacon and Kepner Beacon back into the bureaucratic morass that Magaña and his team fought so long and hard to escape.

And guess who will suffer? Kids and families, of course.