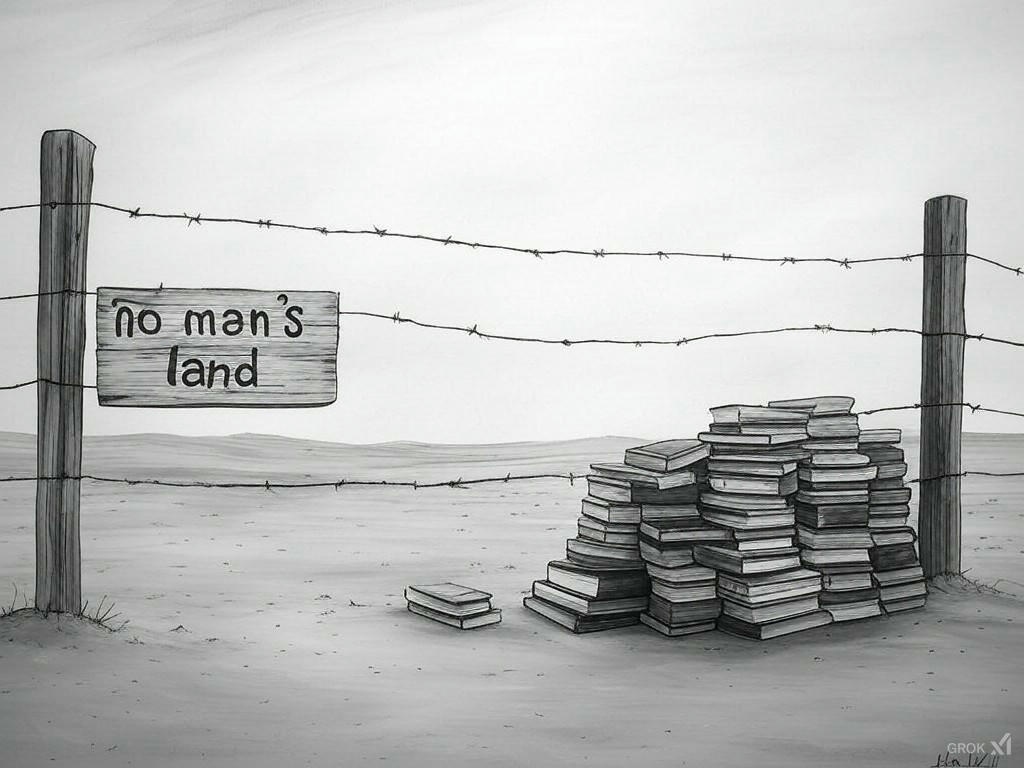

The debate over how Denver Public Schools allocates money to its schools may not seem like the most scintillating topic to address less than a month before a pivotal school board election.

But it cuts to the heart of differing philosophies about school governance and autonomy. Some members of the current school board have made it clear they would like to eliminate or curtail the long-held practice called Student-Based Budgeting (SBB) and replace it with a more centralized, cookie-cutter approach.

One of the leading proponents of axing SBB is Scott Baldermann, who represents southeast Denver and is up for reelection next month.

The simplest definition of student-based budgeting is that it allocates varying amounts of money per-student to schools based on the needs of each student. So, for example, a student from a low-income household brings with her more money than a student from a more affluent family. English Language Learners and special education students also bring more money.

As a result, a school of, say, 400 kids with a high percentage of low-income students and students who are learning English ends up with significantly more money than a school of equivalent size with an affluent school population. In Denver at least, school principals have significant say over how to spend that money.

Here’s an example from this school year’s budgets, using two schools in Baldermann’s district. At Ellis Elementary School, 90 percent of students qualify for subsidized school lunches (an inexact proxy for poverty). Just under half of the students are English Language Learners. Ellis receives $12,724 per student.

Four miles to the northwest, in the affluent Washington Park East neighborhood, Steele Elementary School receives $8,112 per student. That’s because just 10 percent of Steele students qualify for subsidized lunches, and fewer than 5 percent are English Language Learners.

In a recent interview with conservative radio host Jimmy Sengelberger, Baldermann argued that SBB is inequitable and “we’re intentionally underfunding our schools that need the most supports.” He said basing funding in part on enrollment guarantees that low-enrollment schools (many of which are also low-income) are starved of resources, and fosters unhealthy competition for students among district-run schools.

“We have to get away from that idea,” Baldermann told Sengelberger. “We’ve got to fund from the district level, look at the school, look at the needs of the kids, fund that first and then go from there.”

The key words here, it seems, are ‘fund from the district level.’ Take away much of schools’ autonomy over how they spend their money and give that responsibility back to the central office.

Balderman’s logic seems through-the-looking-glass bizarre and backwards to me, so I reached out to him for clarification.

He told me that schools filled with low-income kids are often smaller schools, and additional funding tied to those kids does not make up for money lost by low enrollment. The solution, he said, is to fund programs and staff equally so that all schools get the full array of offerings that only larger schools now get.

He explained his position as more of a “hybrid approach.” Certain essential services that would provide all schools with a “guaranteed student experience” including supports for low-income, English-learning, and special education students, social workers and nurses would be funded centrally to each school. He said this would eliminate inequities caused by under-enrollment.

Anything left over after that reabsorption of funds by the district could be used by principals to decide, say, which electives to offer. He said it makes no sense for the central office to fund custodians but not mental health professionals, as is currently the case.

“That probably means that the portion that goes its remaining for student-based budgeting is going to be much smaller,” he said.

Baldermann also said this approach will only work once the board faces reality and moves to close up to 15 schools in the near future, helping solve the under-enrollment issues at other schools.

Parker Baxter, scholar in residence at the University of Colorado Denver’s School of Public Affairs, says SBB helps level the playing field by providing extra resources where they are needed most. Baxter worked in DPS when Tom Boasberg was superintendent and SBB was in its heyday.

“It is difficult to describe how wrong Baldermann is about this,” Baxter said. “He claims that DPS needs to look at the needs of the kids in each school and fund based on those needs, but that is exactly how the district’s funding model works now.”

Balderman’s approach, he said, would do the opposite of this. “The more important question of equity is to ask how to fund schools of the same size which serve students with different needs,” Baxter said. “Balderman is fantasizing that there is enough money to shift the balance back towards centralization without denying poor kids additional resources. This is impossible.”

Kimbelee Sia, Baldermann’s opponent in the upcoming election, supports SBB. “It helps ensure financial resources align with the district’s goal of meeting the needs of all students and are equitably distributed,” she said.

“The idea that student-based budgeting creates inequity for the district is the opposite of what it is intended to do.”

It seems wise to me to trust principals to make decisions about what supports are needed at their schools, rather than leaving that up to central office administrators who are farther removed from the everyday challenges of running a school.

This is bound to be an ongoing debate after the board election, and it would be wise for the public to pay close attention and make their voices heard.