Colorado school districts mission and vision statement rhetoric about all children succeeding will remain nothing but hot air unless and until they take more effective steps to solve the state’s reading crisis.

That’s the inescapable conclusion reached in a new report by longtime educator Peter Huidekoper Jr.

Colorado is not alone in confronting this longstanding crisis. As brilliantly illuminated by education journalist Emily Hanford’s articles over the past several years, and her 2023 Sold a Story podcast, the education establishment in this country – which includes textbook and curriculum publishers, schools of education, and school districts – has been guilty of educational malpractice for decades, using now-discredited Whole Language methods for teaching reading.

Thanks in large part to Hanford’s reporting, this has begun to change. It’s now common to hear school district leaders boasting about how they are incorporating the “science of reading” into their curriculum.

That sounds great, and is a step in the right direction. But education has a way of sucking promising new ideas into the bureaucratic morass and then regurgitating watered down and ineffective implementation plans.

It’s imperative that this doesn’t happen with reading.

Huidekoper’s report examines Colorado’s READ Act data as well as Colorado Measures of Academic Success (CMAS) scores and PSAT and SAT results. It reveals that while the focus on early literacy mandated by the 2012 READ Act is important, it alone has not resolved the crisis.

Quite the contrary: Large numbers of students in upper elementary, middle school, and high school lack reading proficiency and, if current trends continue, are never going to catch up.

Huidekoper’s study finds that thousands of high school students across the state remain on READ Plans (developed for any student with what is termed a Significant Reading Deficiency) through high school. Even Denver’s flagship East High School had 153 students on a READ Plan in 2021-22.

This severely hampers these students’ ability to enter the workforce with any kind of hope for a bright future. Whether any given student aspires to a college education, a well-paying job in the trades, or anything in between, their chances of success are slim to none if they can’t read proficiently.

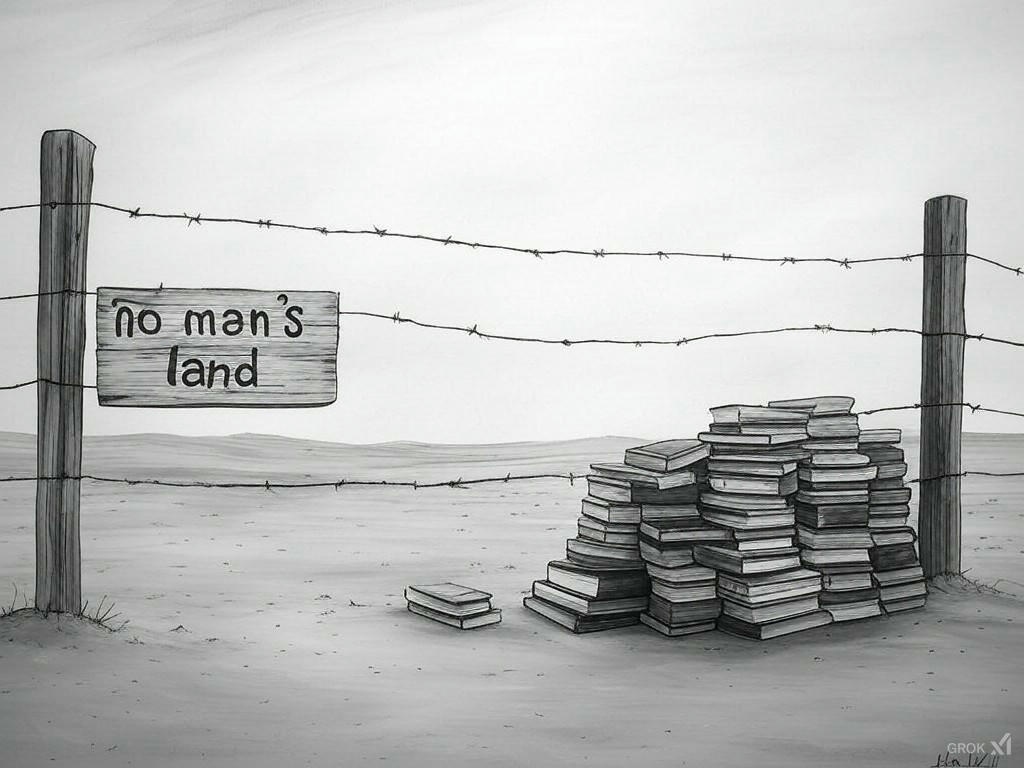

Huidekoper’s report points out that the READ Act’s focus on getting K-3 students to reading proficiency “was never going to be enough…tens of thousands of students in grades 4-12 are terribly far behind as readers and writers.”

He recommends that the READ Act, and attendant resources, be expanded to grades K-5 as a first step. This would mean overhauling the training of teachers so that upper-elementary teachers get the same level of training in teaching reading as the READ Act mandates for teachers in the younger grades.

“It is unconscionable to leave teachers ill-equipped for the job, to just say: good luck. Without the proper training, the task we have given our 4th and 5th grade teachers—again, to address the reading struggles of 30,000-plus students—is impossible,” he writes.

He also argues that the act’s high-blown, unrealistic goal of getting 100% of third-graders to proficiency actually stymies progress because everyone knows the goal is unattainable.

He advocates for setting a more realistic goal of getting 50% of entering sixth-graders to reading proficiency. That’s bound to be a controversial recommendation in that it coinsigns half of students to failure, or something approaching failure.

Huoidekoper’s response? “I believe that once we support our 4th and 5th grade teachers in this way, we can set a new, meaningful target: to see that a majority of our students, and maybe even a large majority, are reading well by the time they complete fifth grade.

“Not ambitious enough, you say? Let’s achieve that goal first – and then raise the bar.”

The report is rich in test-score data and analysis, and is well worth reading. Huidekoper anticipates that some people, in particular anti-testing zealots (including some on the Denver school board) will object to his work because it focuses so heavily on test scores.

“I know some will say this data is too focused on gaps or deficits. That they are overly dependent on biased tests. That many students, especially in high school, feel no reason to try their best on state assessments,” he writes.

“I merely ask: Please do not look away.”