Editor’s note: This is the latest piece by Boardhawk columnist Aaron Massey. See his bio at the end of the article.

I’m going to tell you a story. A story that is quite painful for me to tell but I believe has leadership and policy implications for how we move forward in education together.

For the purposes of professionalism and respect, I won’t share the name of the people involved, school, organization, or city. (No, it’s not Denver). I’m not telling you this story for pity. I’ve reflected, recovered, and learned from that experience and that’s exactly what I want you to do.

On the second day of the Mike Brown protests in Ferguson, Missouri, I marched the streets in mourning as yet another Black boy was murdered. When the pepper spray dissipated, I checked my phone and saw that an organization had reached out to me about being a founding principal at their charter school. I had taught math in that same building years prior when it housed a traditional public school.

They wanted to reopen the school and they wanted me to do it. That traditional public school had closed due to poor academic results and a poor behavioral reputation across the city. Imagine my glee! Returning to the place I learned so much from to lead. Weeks later, I packed my bags and headed there.

I didn’t know much about charter schools. I only knew this was an opportunity to reunite with my former students, former colleagues who still lived in the area, and my former principal whom I stayed in contact with. I learned about the charter network, got to know my executivedDirector, and started reconnecting with families I knew.

“Massey Moolah” (that’s what students called me) you back!? I’m going to send my lil cousin to your school.” Again, imagine how much my heart was filled knowing that I made a big enough impact on students that they were willing to push their little cousins to come to my school. I continued to go door to door talking to families and the responses were similar.

In meetings, my new colleagues were passionate, intelligent, considerate, and ready to do something transformative. The executive director and I had a close relationship. You have to in this type of work. We had to make decisions about the vision and flow of the building, what walls we were going to tear down, and who to hire.

After weeks on the ground, we really started to build some momentum. Besides hiring, curriculum writing, recruiting students and families, and systems building, I quickly took on the role as the face of the school.

Things were going well. That is, until two events occurred.

The first event wasn’t an event at all. Or at least not to me. In a meeting discussing landscape and culture, I made it clear to my whole team that they needed to be aware that the school was situated right in the middle of three rival gangs. Growing up in East St. Louis, I know that it is imperative to know the street politics of where you operate. That statement was quickly hushed by my ED.

I didn’t press the point further in the moment; however I did talk to her one-on-one. I told her that gangs are a very real social network that exist in this community and we needed to be sure to prepare staff for that reality. She didn’t agree. (But she also didn’t teach in that building.)

A few weeks later, we were at a gala where the network of schools was celebrating another successful year. At the gala, the CEO of our organization introduced my executive director and me to some notable funders. The CEO introduced me as the founding principal and her as the executive director. The notable funders took a liking to me and my story – while showing her very little attention.

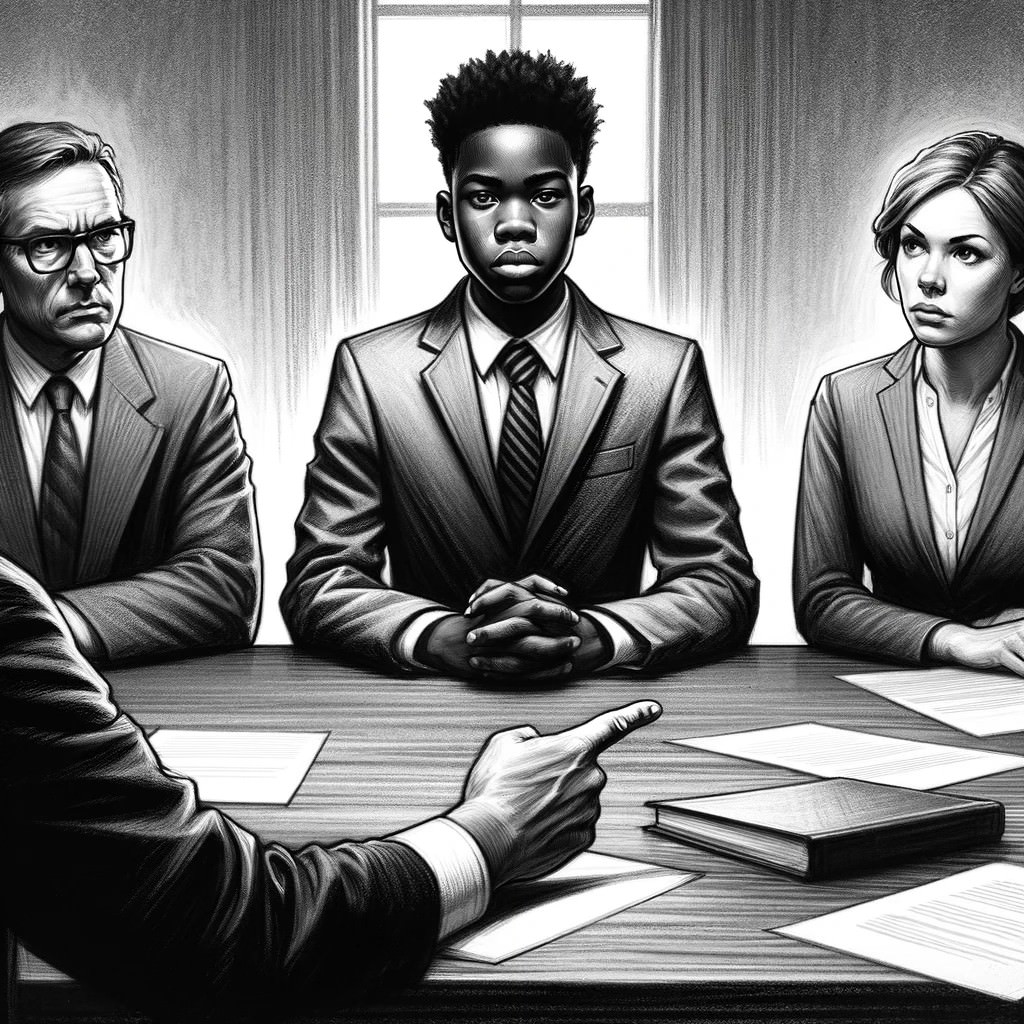

Well, that’s event two. A few weeks after that, I’m called into a meeting to be fired.

If you’re a Black man in education, you can kind of tell when something drastic is going to happen. When I told my highly effective buddy whom I hired that I was heading to get fired, he was in disbelief. Nonetheless, I sat down with my executive director and the head of human resources for the entire CMO and was promptly terminated.

In tears, I asked what I could have done differently, what I did wrong, is this the final decision? Human Resources explicitly told me that I didn’t do anything wrong and they were willing to give me a severance package if I remained quiet about this experience. If I didn’t want to remain quiet, I could simply leave.

Being a broke, young leader, I took the money and left. (And if you’re reading this, you can have your little money back).

It wasn’t until I sat in a doctoral class at Vanderbilt University that I told this story. My professor wasn’t shocked. He went on to tell me that this is not as rare as you think.

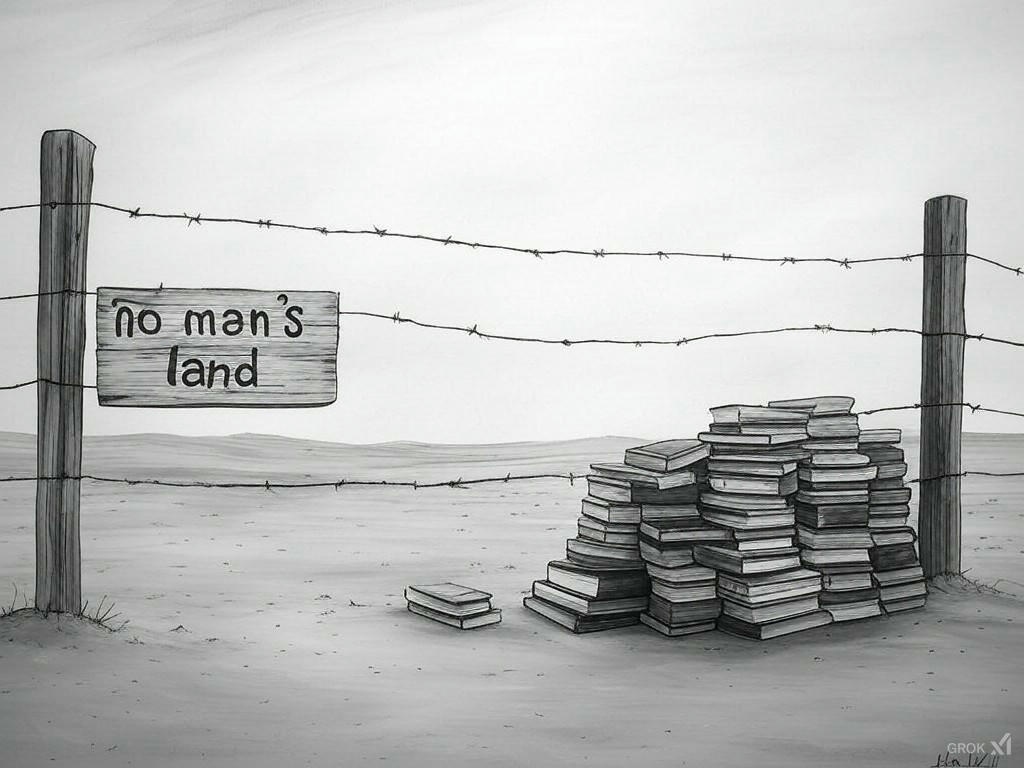

As I sit here writing this a couple weeks away from graduating with my doctorate, I’m reflecting on this situation. No one won in this scenario. The school opened only to close years later due to poor academic results and a poor behavioral reputation across the city (sound familiar?). The staff struggled with less than ideal leadership. The families had no other option but to bus their kids. The kids. The kids experienced trauma like none other.

And I walked away scorned.

But that’s not the end of the story. Just as I said in my last article, what we do with pain is learn from it. What I’ve learned from Vanderbilt is that policy only goes as far as people take it. That knowledge sharing and sense-making go hand and hand.

That how you package the data is just as critical as the data. I didn’t have the situational awareness to navigate the politics of supporting an executive director. In turn, and what my dissertation suggests, she didn’t know how to manage a Black male leader.

Deep listening and bounded autonomy will always be more important than pride and protectiveness. I have at least three more stories that I could share with you. And I’m sure you do too. How you were wronged in some way. Or misunderstood in some way. Treated less than.

The biggest lesson I learned from this experience is that this is people work. Flaws, abilities and inabilities, perceptions, gifts, experiences and all. And at the center of this people work are children that need us to learn from each other. Even if it doesn’t seem fair. There is no policy that teaches you that.

This is my graduation gift to myself. Sharing pain and learning deeply.

Kids deserve for you to learn from your pain. How will you?