At last week’s Denver Public Schools Board of Education meeting, Superintendent Alex Marrero made an impassioned plea for everyone to celebrate DPS students for their performance on state standardized tests.

He suggested that ‘critical friends’ in the community seemed reluctant to celebrate this. “If other folks are not going to celebrate our scholars, you can count on me and my team to do so,” Marrero told the board. “I’m celebrating DPS kids, students of color, because you can see that in spite of what we may hear from some folks, we are closing the gaps, which is the hardest thing to do across the schools.”

If nothing else, Marrero and his team are masters of spin. It’s cynical at best to accuse anyone not willing to laud DPS for continued yawning achievement gaps and subpar student learning of dishonoring Denver’s children.

Marrero is right when he says he will take incremental gains over declines. In fact, giant leaps in performance should be met with suspicion. But there is a difference between incremental and infinitesimal. The degree to which Marrero and his team promoted unacceptable results as a triumph suggests that in DPS today, public relations trumps tough truth-telling.

On the positive side, it is true that DPS students and subgroups of students (low-income students and kids of color) outpaced the state on growth measures in many areas. But at the rate that many DPS students are growing, they will never reach grade-level proficiency. That has profound implications for their futures, and is hardly cause for celebration.

And where Marrero gets his “closing the gap” information is puzzling. I guess it depends on your definition of gaps.

An independent analysis made available to Boardhawk shows that non-low-income DPS students grew far faster than their low-income peers. While low-income students grew at the state median of the 50th percentile on literacy tests and at the 49th percentile in math, non-low-income students grew at the 60th percentile in both areas. Numbers were similarly disparate between white students and Black and Latino students.

That looks like a widening gap to me.

And growth is where the numbers look best for DPS. When you examine the percentage of students in various subgroups who are meeting grade-level expectations, the data paint a grim picture.

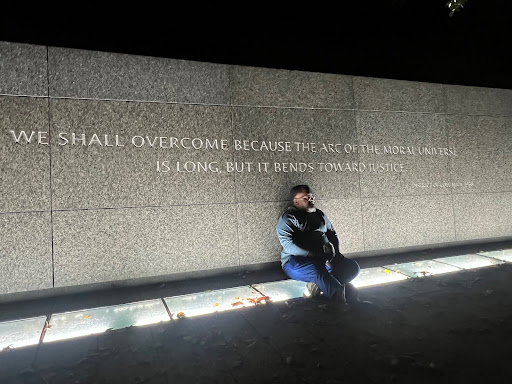

On the English Language Arts state CMAS test, 24.5 percent of Black students and 24.4 percent of Latino students demonstrated proficiency, compared to 73.3 percent of white students. In math, just 16.5 percent of Black students and 15.3 percent of Latino students were proficient, compared to 65.3 percent of white students.

There were similarly enormous gaps on SAT proficiency among 11th-graders.

It’s great that white and non-low-income students do so well in DPS. You wouldn’t want gaps to narrow by bringing down the scores of those kids. But given that the district’s focus over the past few years has been almost exclusively on low-income kids of color, something clearly is not working.

We can re-litigate the old debate about to what degree schools should be held responsible for societal inequities. The fact remains that DPS is doing very little to mitigate those issues.

And yes, standardized tests are imperfect instruments that often reflect cultural biases that disadvantage some students. The fact remains that an imperfect measure is far better than no measure at all, which is what some more extreme members of the DPS board seem to favor.

Marrero’s performance evaluation this year will be based in small part on how students did on standardized tests. He was able to set his own criteria, and the bar was low – a 1 percent improvement on all measures, across the board, means he will have met his goal. From data in the district’s own slide deck about results, it looks dicey whether even that measure was hit.

Educating students in the 2020s is harder than ever. Pandemic learning loss, mental health issues, the pernicious impact of social media, the uncertain implications of artificial intelligence – all collide in classrooms to make teachers’ jobs thankless and grueling. The influx of traumatized and poorly educated migrant students last year made the work that much harder.

DPS needs to be honest with the community about these challenges, and to develop a clear roadmap for incremental, not infinitesimal, improvement that is sustainable over the long haul.

Unfortunately, the Marrero regime seems more interested in burnishing the superintendent’s credentials than in having those hard conversations, either internally or externally.