Sports fans would be apoplectic if the morning paper gave us a story that stopped with the Denver Broncos behind at half-time, 13-7 – and ended there. Or told us that the Denver Nuggets were tied at 58-all as the third quarter began – and nothing more.

Every year the Colorado Department of Education produces its report on the Colorado READ Act. The 2024 report tells us that the state identified roughly 49,000 K-3 students in 2023 with a “significant reading deficiency” (SRD). On Jan. 8, 2025, CDE staff spent an hour-and-a-half presenting their latest results to the State Board of Education. Findings from Year 4 of an external evaluation were also featured.

These annual reports are useful. This year’s account is 67 pages. And yet I have asked myself, why do they always feel so incomplete? So unsatisfying?

It is because they tell us almost nothing about what happens for our struggling readers AFTER third grade.

Which led me to recall Paul Harvey. For decades the famous radio broadcaster entertained listeners by introducing a few key events, then setting us up for a surprise with his classic line, “And now for The Rest of the Story.”

To understand the state’s efforts—the important work taking place in some fashion in all our K-12 schools—to help students achieve grade level reding skills, we need to hear The Rest of the Story.

These reports remind us that, since the Colorado READ Act passed in 2012, the state has provided over $300 million to help students learn to read. More than $26.2 million has been distributed each of the past five years. Substantial “per pupil intervention funds” reach our 178 districts to support this vital effort. In 2022-23 over $7 million went to three districts with the greatest number of students with significant reading deficiencies.

| Denver Public Schools | 3.2 million | 6,045 students |

| Aurora Public Schools | 2.4 million | 4,527 students |

| Jefferson County Schools | 1.7 million | 3,238 students |

The READ Act is designed to support teachers and their students from kindergarten through third grade. In 2022 the legislature added “evidence-based training in the science of reading” for reading interventionists working in grades 4-12. But for the most part, the funding and the work is all about the K-3 years.

And the annual reports reflect that. Herein lies the problem.

Yes, we find the one page in the latest report, per usual, that takes us beyond third grade. It shows the number of students identified as still needing additional support, after third grade, to improve their reading skills.

These students are put on what is called a READ Plan as they head off to fourth grade. Until they can demonstrate their reading skills enable them to read approximately at grade level, they remain on a READ Plan.

Below is data from this one page on grades 4-8, taken from the last three annual reports.

| Grade | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | TOTAL |

| 2021 | N.A.* | 10,777 | 9,584 | 7,904 | 5,813 | 34,078 |

| 2022 | 14,033 | 1,966* | 8,395 | 7,914 | 6,762 | 39,070 |

| 2023 | 12,708 | 10,548 | 2,157* | 6,747 | 6,371 | 38,531 |

*COVID impacted data collection. Incomplete figures.

In a previous piece in Boardhawk, I reported that in 2023 we saw 12,763 students on a READ Plan in our high schools. This 2024 READ Act report confirms such numbers, and reveals something more. It states:

Schools do not receive per pupil funding for students who remain on a READ plan beyond third grade. In 2022-2023, 51,294 students in grades 4-12 remained on a READ plan. Schools do not receive READ Act funding for students in grades 4-12.

So READ Act funds allocate $26 million to help 49,000 K-3 students, and virtually nothing to help 51,000 students in grades 4-12 struggling to read at grade level.

It is not the inequity in funding that is most troubling. It is the abundance of reporting on those first four years, then not a word about what happens from that point on, even as the annual READ Act reports make it clear that the work is not done.

They show that we have not met and will not meet the original goal of the READ Act, “to get children reading at grade level by the time they enter the fourth grade.”

This is obvious when we see that 13,175 third-graders were identified in 2022 with a significant reading deficiency, and a year later, we see 12,708 4th graders on a READ Plan.

In spite of all the hard work by K-3 teachers to address the reading difficulties of their boys and girls, the job is not completed in those first four years.

It is obvious when we see that for the past decade Colorado has never seen 50% –let alone 100% – of our third-graders Meet or Exceed Expectations on the state’s English Language Arts assessment. (True for all grades, 4-8, as well.)

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

| 38.2% | 37.4% | 40.1% | 40.4% | 41.3% | 39.1% | 40.7% | 39.9% | 42.1% |

Knowing this, let’s admit that we are not meeting the challenge, to get students to read at grade level. We have plenty of evidence now to see it was an impossible goal all along. Let’s track our efforts to help these students still struggling to read well. Can we help them become proficient readers by 5th grade? By 8th grade? Before they graduate from high school?

I appreciate that a READ Act report can only be about these first four years. But the Colorado Department of Education owes us something more.

Anji Gallanos, the former Director of Elementary Literacy and School Readiness at CDE, explained to me last year that her unit has no authority to gather information beyond third grade.

“We don’t oversee that (4-12 world) the way we do (K-3).” She was honest about how little was clear, even to her. “What does it mean to be on a READ plan in grades 4-12?” she said. “It could mean anything.”

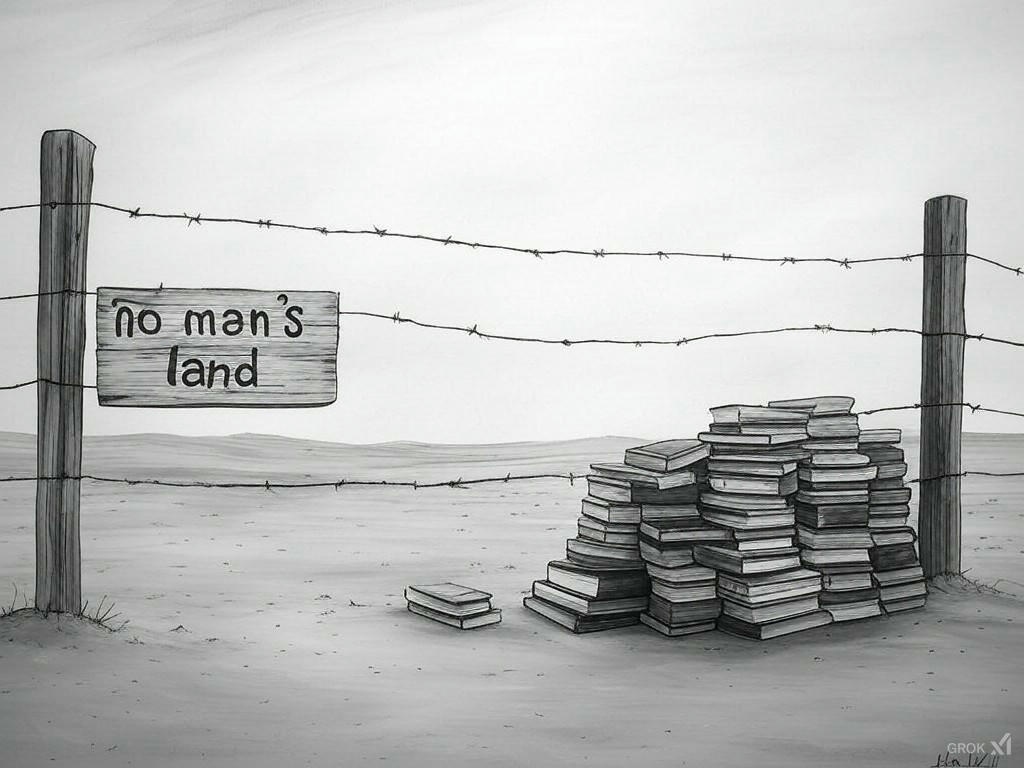

After third grade, she said, “It’s no man’s land.”

For CDE itself, for all of us who want to see our students reading well, the 4-12 years cannot be No Man’s Land. Schools have a responsibility to address the reading challenges of these 50,000 students on a READ Plan. And the state has a responsibility to be transparent about the work. At present, we are in the dark about fundamental issues.

We would like to know, for example, what are districts and schools doing to help these 50,000 students learn to read?

How do teachers in grades 4, 5, 6, and beyond address the reading challenges that prevent their young students from learning the content in their classes?

Where is the training for these teachers in phonemic awareness, fluency, comprehension, or whatever the biggest roadblock might be for each student?

What is NOT happening between grades 4 and grade 9 that leads CDE to report that over 12,000 high school students were still on a READ Plan in 2023?

What is NOT happening, to be specific, between grade 4 and 9 in their school districts that two high schools, Aurora Central and Westminster High, each reported 419 students on a READ Plan in 2023?

Let’s accept that the challenge to see our students read well is one for the entire K-12 system. We need to be realistic and see the size of the problem for what it is. We cannot pretend that a massive K-3 effort will do the job. It was never enough.

All we try to accomplish in the K-3 years is vital. Now let’s hear The Rest of the Story.