Sometimes truth and the dominant narrative collide.

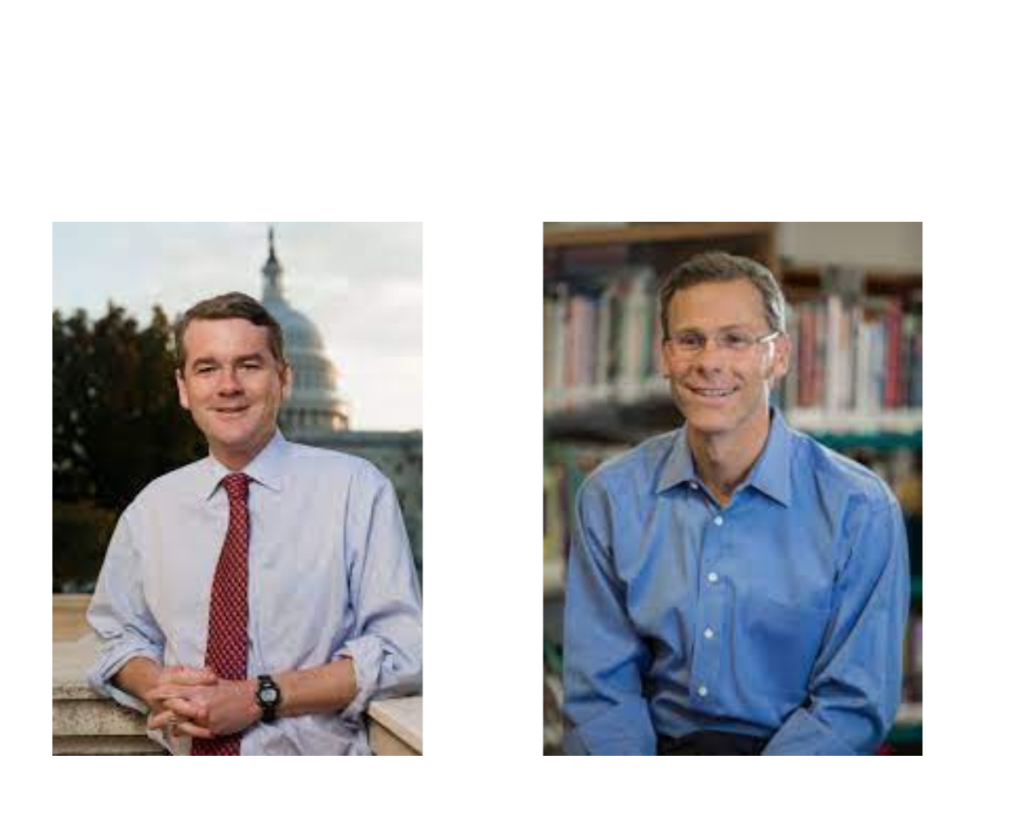

That’s what new research suggests has happened with the legacy of former Denver Public Schools superintendents Michael Bennet and Tom Boasberg.

A consequential study released last week by the University of Colorado Denver School of Public Affairs shows that DPS students experienced unprecedented gains in academic achievement and graduation rates during the so-called reform years of 2007-2019, when first Bennet and then Boasberg served as superintendent.

Notably, the study found that while achievement gaps remained large, students of all races and socioeconomic groups made substantial gains over those years, essentially adding a year of learning beyond what would normally be expected.

“Not only were the district’s reforms among the most comprehensive in American history, they were also among the most effective in size, scale and duration,” researchers found. They used what one of the lead researchers described to me as “state-of the-art econometrics” in their analysis. The analytical methods employed have been recognized for their precision and validity in establishing the causal effects of policy and program interventions.

This is no fly-by-night research, led by ideologically-driven researchers. These are serious academic researchers, conducting rigorous studies. Their findings paint a far different picture than reform critics, some of whom serve on the Denver school board, want you to see.

So it’s no big surprise that the study has been met by thunderous silence from the current administration of Superintendent Alex Marrero and the school board. Board members in particular have spent much of their tenure talking about dismantling internal structures and systems of oppression, while overlooking the fact that DPS still somehow managed to realize unprecedented gains in student learning during what they consider that benighted era.

You can read stories about the study in the Denver Post and on the Colorado Public Radio website. I won’t go deep into the details here. Instead, let’s talk about the finding’s implications for the present and future of DPS.

One of the most significant findings is that during the reform era, contrary to conventional wisdom, low-income students of color, who make up the majority of DPS learners, actually made significant gains in learning. Black and Hispanic students, as well as English learners and students from low-income families, went from far below state averages in 2005 to within a hair’s-breadth of state averages in both literacy and math by 2019.

During that same period, the achievement of white students surged even more dramatically. The rising tide lifted all boats. Some lifted more than others.

What DPS was doing during that period – notably providing a portfolio of school options from which families could choose – worked extraordinarily well for white kids. It also worked for kids of color, just not as well.

The study’s findings suggest that instead of denigrating the work of Bennet and Boasberg, calling it racist, supremacist, corporatist, and oppressive, the current regime and board might want to study why it worked and how it might be improved upon.

I am not arguing that DPS over the years has done an adequate job educating low-income students and kids of color. A huge amount of soul-searching and work remains to be done.

But I am beginning to wonder whether achievement gaps are the best measure of a district’s performance.

People who care about public education should celebrate what DPS accomplished with white students, the district’s second-largest constituency. Surely no one would want to narrow achievement gaps by bringing the top down closer to the bottom.

Instead, we should be trying to decipher what in-school and out-of-school factors are keeping some students from making equivalent gains. Spoiler alert: It’s not all inside-DPS oppression, racism, and white supremacy. There are deeply entrenched societal factors at play.

Another reason people might overlook the real progress DPS made is that the district itself set unrealistic expectations. For example, the district’s previous strategic plan, Denver Plan 2020 (released in 2015), set a goal of having 80 percent of third-grade students at or above grade level by 2020.

Even though the district was making real progress improving third-grade reading – about 2 percentage points per year for low-income kids of color – it started so far from that goal that in 2018, it would have taken 30 years for Black students and 27 years for Hispanic students to hit the 80 percent mark. That’s according to a report by the late, lamented A+ Colorado.

Policymakers should know what’s realistic and set ambitious but achievable goals. It serves no one well to set clearly unrealistic and unreachable goals, setting off an endless loop of perceived failure and recrimination. There’s a fine line between being complacent about inadequate progress and trying to placate people by essentially setting fantasy goals.

The silence from DPS on the new study is discouraging, and suggests that the district would rather ignore credible information that runs counter to its dominant narrative. Perhaps the district and board will say something this week, but I’m not holding my breath.

Meanwhile, other reform critics have also chosen to ignore the study rather than denigrate it. That’s wise. I would hope that any critiques that might be forthcoming are focused on substantive questions about the report’s methodology. Those are always conversations worth having.