I often question myself: Why are you fighting this fight? Why are you still giving yourself to any kind of effort to right things in this school district? My experiences with Denver Public Schools whisper, “don’t you remember what they did to you? To your teammates/friends? To the students you served? To your family? Don’t you see what is still happening?”

For many black people, our engagement with the oppressive structure and systems that are DPS is a constant reliving of our trauma, our hurt, and the pain of being pushed out, down, shamed, and blacklisted by oppressors who feared our vision for liberation, daring to learn and live beyond their reach. Such a structure and systems always want us in our place and our place was never to challenge the structure or the systems. Good thing I was raised for a different place.

The first piece in this series, what I identified as historical framing, a gentle look at the road that brought us here, was called “black on black commentary” by one reader. Some questioned my support of black women leading the work within the district. My mother, a black woman who has been a part of this district for over 50 years as a student, parent, teacher, and current school leader, thought that was laughable. My aunt, a black woman, over 50 years the same, a retired educator, remarked, “the nerve of some people.”

This call out, this pulling back of the veil, isn’t targeted at individuals. It is aimed unapologetically at a structure and systems not designed for the good of black children. If you protect said structure and systems, then you will be offended at every turn of this piece. I promise that without apology. It is intentionally done. You should be offended and so much so, you should quit, resign, take up another profession, because we refuse to continue this way forward.

The truth of the matter is that the organization I serve in and through, FaithBridge, met with the district leaders in January 2020. Seems like ages ago because of this pandemic. I note that those that we met with are individuals that have been in the fight and have my respect because I know the environment in which they fight.

From that meeting with us, and some community stakeholders that attended, the clear message was that nothing was moving unless we pushed together. Actually, what was said to us in that meeting was, “it’s time to rip off the band-aid and deal with the real realities of the black experience in Denver Public Schools.” Rip off the Band-Aid. That’s like telling a hunting dog to hunt!

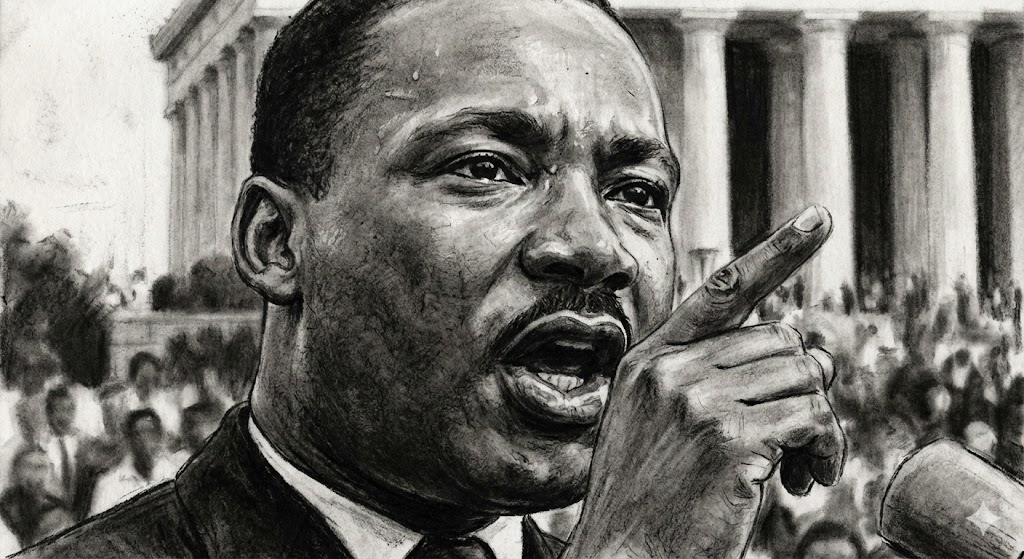

Expose the rhetoric. Talk about the lack of progress because of continual turnover. Talk about the internal bureaucracy. Point out the privilege that still sits in decision-making roles. Call out the white moderates of the district who still pander to voters and donors of privilege. Don’t whisper it but shout it from the mountain tops: “We are not serving black children, families, teachers, and leaders well in this district.” Don’t back down, stand firm, and rip off the band-aid that has been used to cover infected, open wounds, that will not heal unless we do. These open wounds have developed a stench because they have been ignored, decade after decade, by people who spray the Febreeze of social privilege and supremacy.

It is in that spirit, in support of those leading the work, and the many who have been unjustly pushed out of the work in Denver Public Schools, that we continue this series and look transparently at what has been accomplished since 2016, the task force recommendations of 2017, and more recently since 2019 when the Black Excellence Resolution was passed.

Y’all remember what I said, “with all deliberate speed.” When it’s comfortable. When it’s profitable.

2016 – Bailey Report & Bailey Resolution of 1995

The Bailey Report is more than words on paper for us. It’s a snippet of truths that we were told not to tell, whispers of what we shared openly in safe spaces. It is a capturing of lived realities of black people in district-managed and charter-managed schools. The Bailey Report is evidence that from 1995-2016, the district did not prioritize the learning of black students, nor the professional and personal realities of black teachers and school leaders.

The Bailey Report is proof that the Bailey Resolution of 1995 was not carried out with fidelity and any action taken within the district only contributed to enough gradualism and incremental change to appease the masses. It’s like the student growth narrative. Be okay with slow progress because at least we’re growing towards being who we should already be. You should already be proficient in equality and equity serving children and families. You would think. But, with all deliberate speed. Points for trying. No accountability for failing.

The superintendents in that window (1995-2016), excluding acting superintendents, were all white males: Moskowitz (1994-1999), Zullinger (1999-2000), Wartgow (2001-2005), Bennet (2005-2009), Boasberg (2009-2018).

Acting Superintendent Cordova invited individuals to participate in the Bailey Report study in April 2016. Twenty-one years from the Bailey Resolution (Board Resolution 2529 – see page 68 of the Bailey Report for full text), there is a commissioning by an acting superintendent, to explore why we were STILL failing black children, families, teachers, and leaders. Not commissioned to figure out why it had started, but why was it continuing. Grapple with that. Chew on that truth.

The Bailey Report gives birth to the African-American Equity Task force

2017 – Task Force Findings (African-American Equity Task Force Guidelines and Recommendations) Read those when you get the opportunity. Let me just pull out a point. After the very thorough look by the Bailey Report, the task force began another seven-month process to “engage in deep, authentic and meaningful internal and community-based conversations.” Even armed with the powerful Bailey Report, the district’s approach is more conversations, as if we have not already identified root causes and didn’t know the immediate steps to take.

No immediate transformation of the structure and systems that were sustaining the grip of supremacy ideology on the district and the destinies of black children. Not because black leaders internally weren’t pushing. Not because black leaders externally weren’t pushing. Things remained the same because things were designed to operate that way. No broken structure or systems here. They were operating as designed. Neglecting, by design, the same communities. Negating, by design, the brilliance and boldness of black teachers and leaders. Never changing, by design, beyond the rhetoric, and a sprinkling of appeasement here and there.

The task force reported out:

“Based on these thoughtful and robust conversations, as well as extensive research into ongoing disparities and root causes, the working groups have developed specific recommendations for defined levers of impact that will enable DPS to more effectively address opportunity and achievement gaps for African-American students and educators. Based on these levers of impact, the recommendations have been grouped into the following:

I. District and School Structures to Promote Equity

II. Culturally Responsive Instruction, Engagement and Communication

III. Targeted Supports for Students

IV. Community and Family Resources

V. Equitable Employment Practices and Work Environments”

The task force provided a summer update in 2018 of their achieved progress while dealing with internal resistance at all levels.

The Black Excellence Resolution is passed in February of 2019 calling for transformation at the school, district and central office levels. Progress updates, as of May 2019 are posted on the Culture, Equity and Leadership Team (CELT) website. Please read them. (Note: I have a scheduled meeting with members of the CELT team on Friday, May 8, 2020 to discuss more accomplishments that may not currently be articulated on the website.)

There is a lot there in the stated accomplishments. A lot of pushing. A lot of personal sweat and struggles against a structure and systems that refuse transformation. A lot of careful navigation. Cosmetic upgrades in so many ways. You read through them and many things have taken place in the central office bucket, but in conversations with school leaders, few things have transformed in buildings because of a lack of understanding of what is required, capacity to implement, and as some honestly admitted, lack of support and accountability.

The district itself is still struggling to define equity. Still struggling to define a shared vision forward with a comprehensive strategic plan to get there together. Too many departments, committees, sub-committees, and parts operating in silos, disconnected from the reality that we must align our brilliance to do what is better and best for black children and therefore all children served by Denver Public Schools.

How many schools have had equity audits? How many schools have co-created their equity plans with their communities? How many schools have legitimately improved their suspension data by shifts in practice, not reporting? Where are the black teachers and school leaders?

If the Bailey Report II were done today, would the results be any different than they were almost four years ago?

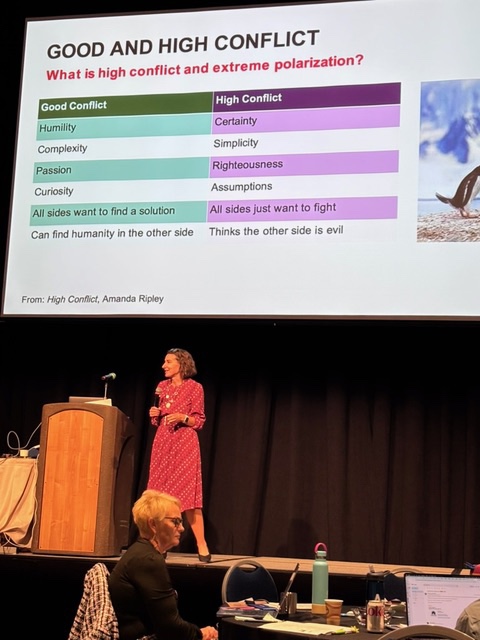

We are not satisfied continuing the “with all deliberate speed” approach. It’s time for folks to be made uncomfortable. It’s time for courageous actions, because we have talked long enough. We’ve graciously explained the impacts of supremacy ideology over and over again, as if the listeners didn’t know.

The demand for structural and systemic transformation has to happen now, period. We’ve heard ‘wait’ long enough. There’s a lot on paper. It’s time to keep our promises. #keepourpromises