What Denver Public Schools calls innovation can look like a number of things, all of which require some flexibility.

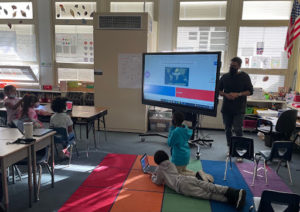

At the Center for Talent Development, a central Denver elementary school located in the former Greenlee Elementary School building, innovation can look like classes with kindergarten, first and second grade students together. It can look like language arts and history being fused into a humanities hybrid.

Innovation—which under state law is a way for schools to exercise instructional, administrative, and scheduling autonomy—at CTD can also look like a colorful, beanbag-chair-filled library designed with the help of students themselves, or a schedule that provides teachers with a non-teaching afternoon once each week for planning purposes.

“We’re going to find kids’ talents wherever,” CTD Principal Sheldon Reynolds said. “If it’s language, leadership, arts, athletics, we’re going to expose kids to all this stuff, find out what their talent is, and try and tap it.”

But the talent development model of education goes beyond this one school’s walls.

It starts with a standardized test that purports to measure giftedness. Students deemed gifted after taking those tests tend to be disproportionately affluent and white, an issue that has long raised questions about biases baked into the test.

“It’s one of the best assessments out there, but it’s still culturally biased,” Reynolds said, holding the test in his hands. “These kids are gifted, (but) this test is never going to say that, so we need to find whatever talent they have, tap on it and teach as if they’re formally gifted.”

The Center for Talent Development educates an 85% minority student population.

To attend the school, students do not have to score at a particular level on a given test. The school also considers teacher recommendations from other schools, performance on the Colorado Measures of Academic Success (CMAS) tests in math, English language arts, science and social studies, as well as other diagnostic tests in areas such as nonverbal ability, math, or literacy.

“If your child has not yet met these requirements, don’t worry,” the school’s website reads. “We offer universal Gifted and Talented instructional practices for all students during core instruction.”

Those last two words—core instruction—are the students’ academic courses. It takes up one part of their week, while “advisory” takes up another. During the advisory period, Reynolds said, students are attending talent development classes of their choice.

Those last two words—core instruction—are the students’ academic courses. It takes up one part of their week, while “advisory” takes up another. During the advisory period, Reynolds said, students are attending talent development classes of their choice.

The school offers music, dance, athletics, languages and leadership courses, and sometimes can merge some of these non-academic subjects based on students’ interests.

One day last week, a group of students was learning dance moves in the school’s auditorium. Music and theater had been combined with physical education, Reynolds said, because the students and teachers wanted to put on a musical.

Another class, called “traveling around the world,” is taught by Abel Blancafort Simón, a Spaniard who wanted to use his own experience as a world traveler to educate his students. And ballet classes are overseen by a teacher who did not know ballet herself, but who had the idea to partner with a dance school just down the street.

“American Sign Language,” is offered, Reynolds said, “because we have one teacher who kind of adopted her niece, who’s deaf, so she’s been learning sign language.”

Another group of students, in an art class, were coloring, drawing or crafting. There was no specific assignment. First grade teacher Nikkole Strahan explained why.

“We’re finding our inner peace today,” she said.

Asked if the school had anything special planned in honor of Black History Month, Reynolds said he and the staff have a mission to build Black history into the curriculum throughout the year. Books students read and study have Black lead characters. Quotes on the classroom walls come from Black and Brown world leaders.

Reynolds said the school does “three weeks of instruction and then a week of culture.” He said this last week—a “culture” week.

It’s a week during which instruction and assignments are focused heavily on identity development, Reynolds said. Students can reflect on how they see themselves and how they feel seen by others, and they have the opportunity to learn about places and people who share their cultural identity.

Additionally, every Thursday is an early release day for students. Thursday afternoons are reserved for Reynolds, administration, faculty, and staff to get together and plan curriculum.

In January, DPS board member Scott Baldermann proposed limiting the autonomy of innovation schools like the Center for Talent Development by requiring them to adhere strictly to most of the collective bargaining agreement negotiated by the district and the Denver Classroom Teachers Association.

The policy outlines a uniform school calendar and a rigid regulation of teacher hours and duties.

Some innovation school teachers, who rely on flexibility in terms of hours and teaching duties, have said they do not understand the board’s reasoning.

“We work hard, we’re here, and we do pack it all in, but we’re really thankful for the time that we have on early release to plan,” CTD counselor Katy Wafaie said. “We don’t feel like we’re missing hours.”

During last week’s planning session, a teacher asked Reynolds what he thinks the DPS board’s goal may be.

Reynolds wasn’t sure, but said his concern is that it’s not clear where the policy is coming from or what issue it could be an attempt to address. He said if there was a problem with innovation schools’ calendar, for example, he’d be willing to participate in that discussion and show how his school uses calendar flexibility.

But no one has pointed out a specific issue, Reynolds said, that both applies to innovation schools and would be addressed by such a policy. He likened it to a government slowly chipping away at certain people’s voting rights—restricting the days on which people can vote or the methods people can use—under the guise of making the process more equal.

“They weren’t talking to people in innovation schools to see what was going on,” Reynolds said. “We’re dependent on innovation. We’re dependent on all this stuff.

“Why are we having to defend it?”