Now that the 2020 election is over, it is clear that some educational demands must be addressed in this next Colorado legislative cycle.

More than ever, adjustments to educational norms to address inequities in curriculum, assessment, and instructional practices must be prioritized to make these shifts happen. Student engagement, parental inclusion, and community involvement should be at the center of these shifts.

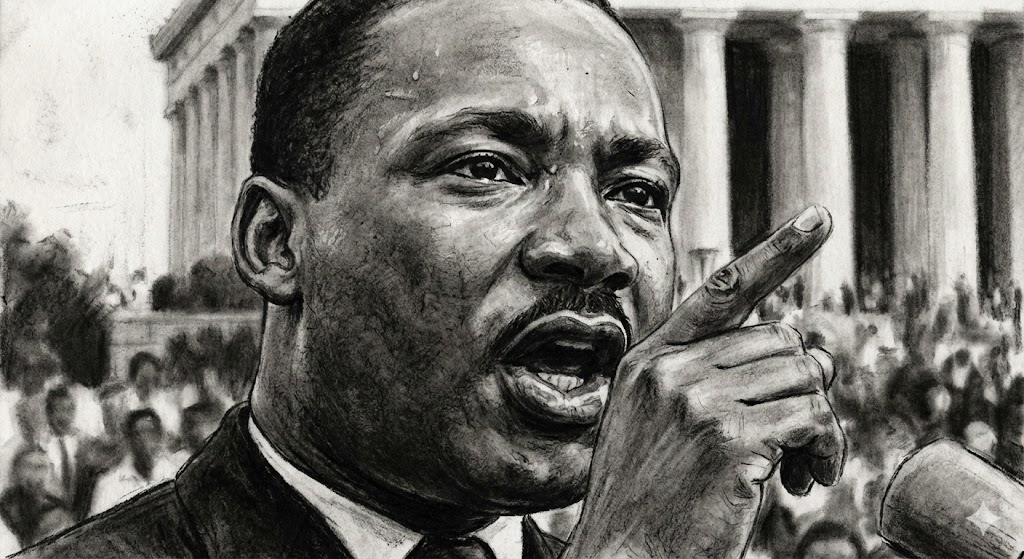

It is time to begin dismantling existing curriculum anchored in the overrepresentation of Eurocentric thought and perspective. Throughout history, prominent educators such as WEB DuBois, Carter G. Woodson, Paulo Freire and other philosophers of color developed ways for this kind of secondary and post-secondary education to be developed.

Early in the 20th century, these educational philosophers developed blueprints for how humanities and social science education could provide a more inclusive, diverse, and equitable approach. Yet, we find ourselves in 2020 still perpetuating Eurocentric philosophies, perspectives, language, and versions of history in our classrooms.

In October, the Denver Public Schools board approved the youth driven resolution “Know Justice, Know Peace” with specific calls to action for changes in curriculum. These included action to “ensure that all schools within the family of Denver Public Schools’ curriculum and professional practices include comprehensive historical and contemporary contributions of Black, Indigenous, and Latino communities.”

Students specifically called within the resolution to have race emphasized throughout the curriculum and not within specific cultural courses. They emphatically stated that racial lenses must not be confined to one course, but available to all students in all courses.

To make change for our students, we must revamp the approach and mindset of curriculum development and subsequent teacher development.

As an eighteen-year literacy specialist, coach, and former humanities teacher, I know far too well the feeling of trying to bring Black history and literature initiatives into my classroom and being the only teacher to have these kinds of discussions with my students. This must change.

James Baldwin, in 1965, addressed why instructional practices need to address race:

History, as nearly no one seems to know, is not merely something to be read. And it does not refer merely, or even principally, to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do. It could scarcely be otherwise, since it is to history that we owe our frames of reference, our identities, and our aspirations.”

As we make shifts in curriculum, we must prioritize the development of students as “intellectuals” through an exploration in our classrooms of self within literature, history, and contemporary issues. So often, attempts at “representation” and multi-perspective history have been limited to multicultural literature and monthly cultural celebrations.

However, to truly prepare our students for their futures, we must laser-focus instruction through critical thinking within anti-racist and culturally responsive lenses. We must accomplish this through challenging the mainstream idea that culturally responsive instruction and the inclusion of multicultural literacy and cultural history are not rigorous.

We also must challenge the mindset that it is not our job to explicitly teach critical thinking to our students. It is imperative, more than ever, for their economic survival.

According to The Future of Jobs Report of 2018 by the Centre for the New Economy and Society, skills such as analytical thinking and innovation, active learning, creativity, problem solving, critical thinking and emotional intelligence have emerged as the top skills people will need in the workforce by 2022. Conversely, memorizing and basic comprehension and writing abilities will be declining skills in 2022.

This shows that in making shifts in humanities instruction, curricula must be intentional in helping prepare our students for this changing world through the content we place in front of them in all classes. Culturally responsive instruction is how we develop students as critical thinkers who are aware of their space within their communities.

Students must develop their own judgments about the world they are inheriting by analyzing history and how it applies to what is happening in our contemporary world. They must also be able to read these varied experiences through the literature we ask them to digest.

If students are to understand exactly what happened to George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, or Michael Brown, they must understand the history of policing in this country, the laws and policies from redlining that barred people of color from access of wealth in the 1930s that created the racial wealth gap, and the laws that need to be developed to turn this oppression around. Culturally responsive instruction is critical thinking!

In addition to extending culturally responsive instruction through critical thinking across the curriculum, we must also ensure that opportunities exist within school programming for students to choose areas where they want to continue to build their learning about specific cultures.

We must offer our student electives such as financial literacy, cultural studies, civic engagement, creative writing, spoken word training, musical expression and training. These courses help build students’ awareness of their abilities to be innovative, learn new creative skills, deepen their understanding of cultures, and more. What we offer to students must contribute to their development as citizens in our country.

Currently, at DSST Public Schools, I am piloting a Black Studies course. I have designed the curriculum to feature the resistance movements that remain absent in most classroom discourse and history. As an example, students, teachers, and I have discussed the election season in 2020 by analyzing the work of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party of 1964, which effectively put pressure on the Democratic Party to dismantle segregation and voter suppression in the South.

Students explored how voter suppression has taken shape in this country since Black men received the right to vote when the 15th Amendment was passed in 1867. They examined literacy tests from the South. We discussed the economic implications of poll taxes, and how the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was directly influenced because of the work of women such as Fannie Lou Hamer and Ella Baker– names many of our students have never heard.

Their work directly affects the work that Stacey Abrams, Alicia Garza, and organizations such as the Colorado Black Women for Political Action in Colorado have done to deliver this election. These discussions must take place in our curriculum. They must take shape in our secondary schools, now.

Beyond the work schools do to dismantle business as usual in our curriculum, we will need to also push our legislators and policy drivers to cement changes that affect our students’ lives. It is time for legislation that gives credit for high school courses that prepare our students for the world they will inherit.