In the 2019 New York Times article, “There is a Right Way to Teach Reading, and Mississippi Knows It”, author Emily Hanford noted that according to the most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), a standardized test given every two years to measure fourth, eighth, and twelfth grade achievement in reading and math, revealed that Mississippi made more progress than any other state.

Most notable in the NAEP report was that Mississippi achieved significant gains in the fourth grade reading scores. Hanfield posited in that article and others such as “Why Are We Still Teaching Reading the Wrong Way” and “At a Loss for Words” that the reason Mississippi has seen these significant gains is because Mississippi was one of the first states to ensure that all elementary teachers were trained in the Science of Reading approach to reading instruction.

Beginning in the 2020 legislative cycle, states began to follow Mississippi’s lead by passing similar legislation. This included Colorado, which called for all elementary teachers to be trained in the Science of Reading.

The Colorado Department of Education (CDE) provided that training to teachers across Colorado in an asynchronous format this year based on that legislation.. Because elementary school teachers across the state are being prioritized to meet the 2022 state deadline, the training has not been made available to secondary educators.

Currently, legislative bill HB21-1129 calls to extend this deadline for teacher training to 2022-23, which will allow CDE to offer the training more broadly beyond 3rd grade.

The term “Science of Reading” refers to the research that reading experts have conducted on how people learn to read. Their research found that phonics instruction is at the heart of best practice reading instruction. The science of reading includes a systematic way for teachers to understand the processes of building a lifelong continuum of reading development.

Beyond elementary, this understanding has rarely been offered in schools of education for secondary educators, so as students are sent from grade level to grade level, not having learned to read fluently in elementary school, secondary teachers under most circumstances cannot close those gaps once students present with reading difficulties.

It is critical that CDE be given the funding and ability not only to extend the access to this training to elementary teachers in order to build stronger foundations in our educational system, but also open up access to secondary (grades six through twelve) literacy teachers who wish to develop in this way as well.

I speak from the secondary perspective. Starting out as a student teacher in Metro Nashville Public Schools in 2003, I acquired my secondary English Language Arts licensure after completing my teacher training which included student teaching. I taught both seventh and ninth grades.

During that training, I was given resources and strategies for teaching literature; however, during that student teaching experience, I recognized very quickly that many of my students were not equipped with basic reading skills to read the texts I wanted to teach, and, this could most definitely impact them for the rest of their adult lives.

I knew that my lack of knowledge was to the detriment of my students’ skills, and, ethically, I was not OK with that. Prior to getting my first teaching job that following fall, I completed my undergraduate degree and immediately enrolled in graduate school to study the science of reading instruction.

Then, there were no real pathways for secondary ELA teachers in this space, but the foundational information specific to elementary school that I received during my graduate program gave me the tools I needed not only to support all of my students’ reading development , but also design scaffolds or personalized instruction to increase my students’ reading abilities.

I learned then the importance of phonics instruction and the progression from sounds to words, to phrases, to sentences, to paragraphs, and so on. These foundational facts changed the way I approached teaching middle and high school.

Because of that training, I became a high performing ELA teacher at both the middle and high school levels in Tennessee. I also served as a reading specialist, literacy coach, and district and state trainer in providing this instruction to secondary teachers. Through that experience, I have visited classrooms where teachers entered the profession with some of the same concerns and challenges I had when I was beginning my career as a teacher.

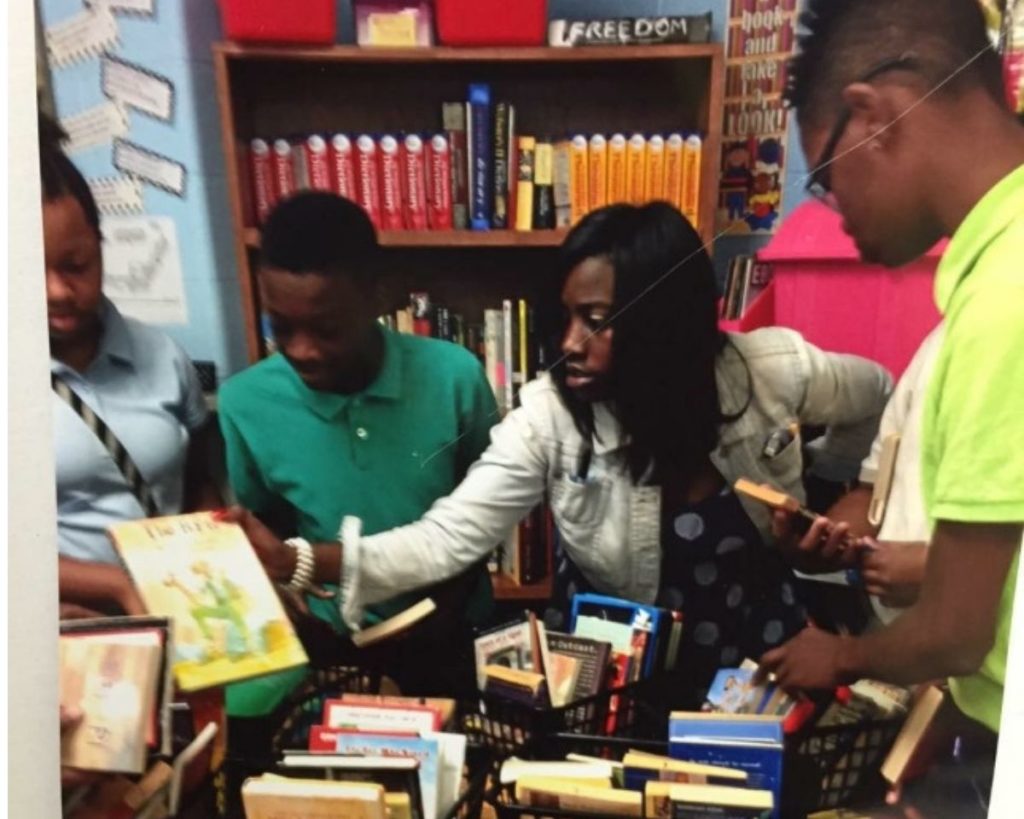

I had the opportunity to consult with a middle school in Aberdeen, Mississippi right at the beginning of their elementary implementation of the science or reading. I helped structure the school’s intervention programming focused on word study including the progression of phonics and phonemic awareness through various stages of reading.

That instruction, coupled with other reading components (fluency, composition, comprehension, vocabulary development) helped close gaps for secondary students very quickly. For our middle school and high school students to graduate as literate citizens, we must know exactly how to provide a strong reading foundation, but also understand how to close those gaps.

To survive in the workforce in coming years, students must be critical, analytical, and creative thinkers– this is not achievable without the ability to read. This is a priority.

The National Education Policy Center agrees with this sentiment saying in a statement in May 2020 that

[…] this key idea of a “balanced literacy” approach stresses the importance of phonics, authentic reading, and teachers who can teach reading using a full toolbox of instructional approaches and understandings. It is strongly supported in the scholarly community and is grounded in a large research base […] at the very least, federal and state legislation should not continue to do the same things over and over while expecting different outcomes. The disheartening era of NCLB provides an important lesson and overarching guiding principle: Education legislation should address guiding concepts while avoiding prescriptions that will tie the hands of professional educators.

The statement emphasizes that all students deserve equitable access to high-quality literacy and reading instruction. Thus, it is imperative that our teachers in grades K-3 especially, but extending to sixth through twelfth as well, understand the basics of how students learn to read and what teachers can do individually to ensure students receive research-based instruction.

I support the continued CDE training offering, and advocate that CDE extends this access for all Colorado teachers. In light of expected learning loss due to the educational response to the pandemic, this training is critical now more than ever.