Denver’s school board is now completely controlled and managed by the teachers union and a traditional, top-down superintendent.

There is no ambiguity about the direction of the district for at least two election cycles. The district is rapidly moving away from portfolio management and toward a more conventional model in which schools are designed, guided, and tightly managed from the central office.

The early signs are clear. The Beacon Innovation Network has been dissolved, and it is reasonable to assume that most remaining innovation schools will be absorbed by the district within the next year or two.

Charter schools will increasingly be treated as they are in many other districts: less as partners in public education and more as competitors or threats to district stability. Charter schools housed in district buildings will likely face the biggest challenges and increased operational friction, making their continued success more difficult.

For many education reformers, this moment marks not only the end of portfolio management in Denver but the end of any real hope for sustained academic improvement, particularly for low-income students and students of color.

While I remain a strong proponent of portfolio management, that conclusion is too simplistic and ultimately too pessimistic. There is still reason for cautious optimism, even under a centralized governance model that many of the reformers of the last decade instinctively distrust.

Traditional, centrally managed districts, when led well, can improve student outcomes. A coherent instructional vision, strong curriculum alignment, and consistent classroom expectations matter enormously. History shows that some districts and even entire countries have achieved meaningful gains by committing to a relatively uniform model of teaching and learning and executing it relentlessly well.

Denver’s own experience with portfolio management did deliver significant academic gains for low-income students for more than a decade. But portfolio strategies are not silver bullets. Detroit and Milwaukee demonstrate that expanding choice and autonomy without strong accountability, quality control, and system coherence can produce chaos rather than improvement.

Strategy alone never guarantees success.

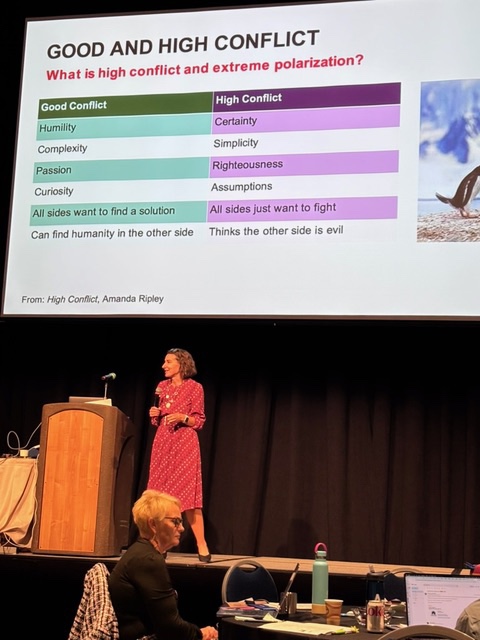

Too often, actors in the school reform wars lose the plot. They argue endlessly about governance structures (maybe the mayor should run the schools?), charter expansion, curriculum frameworks, or funding formulas while losing sight of the central question: Are students learning more?

There are many paths to improvement, and the difference between success and failure often lies not in ideology but in execution, leadership quality, and disciplined monitoring of outcomes. It is entirely possible, though far from guaranteed, that Denver could produce results under Superintendent Alex Marrero like those achieved under Bennet and Boasberg, using very different strategies.

Long Beach Unified in the late 1990s offers a powerful example. Superintendent Carl Cohn drove dramatic gains –20 percent or more on standardized assessments, higher graduation rates, improved attendance, and increased college-going-through a tightly managed, centrally directed system.

Clear districtwide standards for literacy, the end of social promotion, and disciplined instructional expectations defined the work. Importantly, this was done in collaboration with the teachers’ union, but with little ambiguity about instructional non-negotiables. Even charter-focused reform foundations took notice; Long Beach won the Broad Prize as a result.

Similar approaches have yielded results elsewhere: Los Angeles under Alberto Carvalho just this year, Roy Romer’s literacy-driven reforms in LA in the early 2000’s, and Alan Bersin’s prescriptive but initially successful tenure in San Diego also several decades ago. These examples suggest Marrero is not operating without a playbook. It appears that one of Marrero’s models of leadership is Alberto Carvalho who did an exemplary job in Miami and has made improvement in Los Angeles just this last year.

For full disclosure, I remain deeply skeptical of one-size-fits-all systems. Centralized models often impose a ceiling on students whose needs, interests, or learning styles diverge from the dominant design. Denver benefited enormously from schools like Denver School of Science and Technology, Odyssey, and the Green School— models that would never have emerged from a uniform district template.

Portfolio management also allows for a richer array of choice for families so that they are not stuck in their local school but could attend a school that better suits the students and family’s needs.

Ultimately, governance structure matters less than disciplined execution and an unwavering focus on student outcomes. Lose sight of students while arguing about means, and failure is nearly guaranteed. Denver like many places is has sometimes been stuck on fighting issues like innovation schools rather than students.

If Denver’s new board and Marrero adopt the best versions of centralized systems while monitoring student growth it may not become the disaster most reformers expect. And if Marrero succeeds in driving gains for Black and Latino students, it might even help him land his dream job back in New York City as the commissioner.

While still an unlikely scenario, Denver’s teacher union win could turn out to be a win for everyone — particularly Denver’s students.