Denver school board member John Youngquist is alleging that the board violated state open meetings law by misstating the purpose of a recent executive session, and by excluding him from that session because it dealt with a matter he had raised about his compensation.

Commentary

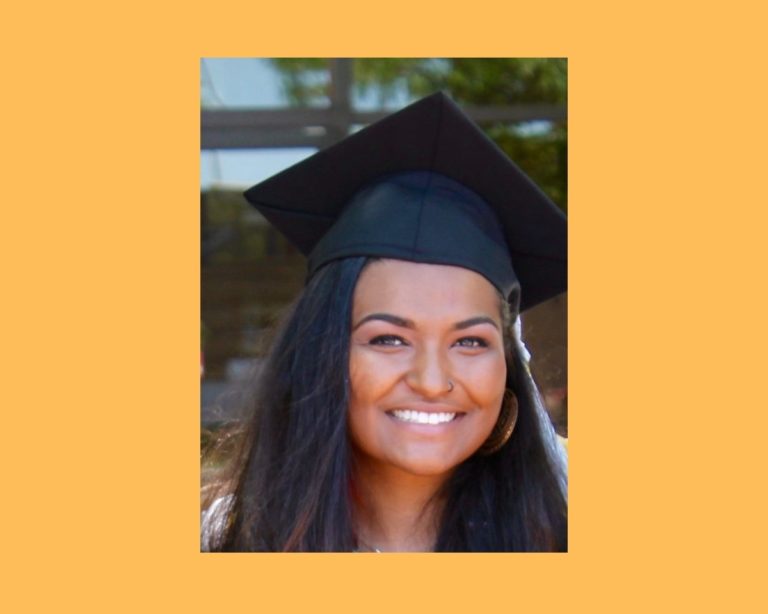

These women, these brown women, mattered to me and made a difference in my educational journey. We should celebrate them this Women’s History Month for all of the lives they have touched.

I learned then the importance of phonics instruction and the progression from sounds to words, to phrases, to sentences, to paragraphs, and so on. These foundational facts changed the way I approached teaching middle and high school.

If we can at least agree that the 2020-21 school year has exacerbated opportunity gaps and increased the likelihood that students suffering the consequences of those gaps have fallen farther behind their more affluent peers, then optional, full-time summer school provides an obvious, if partial, remedy.

After last week’s Denver school board work session, charter school students, parents, staff, and boards have legitimate reasons to worry about their future in Denver Public Schools.

I think it’s essential for young people to understand the value of savings, credit, interest rates and investing to build the future every one of us deserves, and attain generational wealth.

In the days before mandated state testing, schools could hide their dismal service to these children behind vague, aggregated data that masked opportunity gaps from public view.

I have now had direct experience with what many educators have known for decades: No two learners are created equal. And like most parents, I have a new appreciation for the work of our teachers, para-professionals, student support counselors and administrators.

While I love highlighting all things Black, I know that equity doesn’t come through Black history month. Equity comes from listening to the needs/desires of community, being accountable to community, and taking action to make systemic change happen.

I challenge my fellow immigrants to develop an understanding of oppression that Black Americans face in this country. I believe it starts with education.

STRIVE Prep should be integral to a reimagined Montbello campus

It has been unsettling to our families and staff that until now, the conversation about our fate has been avoided in the Reimagining Montbello process. Our families are part of the Montbello community.