Denver school board member John Youngquist is alleging that the board violated state open meetings law by misstating the purpose of a recent executive session, and by excluding him from that session because it dealt with a matter he had raised about his compensation.

Commentary

As Wednesday’s shooting of two administrators at East High School demonstrates in the starkest possible terms, the decision by the Denver Board of Education to remove school resource officers from high schools in 2021 was a grave mistake, and one with tragic consequences. Not surprisingly, no one involved is acknowledging this, at least not publicly.

Why does DPS want to put an end to an organization that is showing promise? Power and control seem to be the answer.

The school board might close three severely under-enrolled schools, and members are getting along, but they continue a drive toward less transparency.

The DPS board and leadership seem more interested in imposing their will and reining in innovative practices than in focusing on what we at Beacon Network Schools are doing to serve our students.

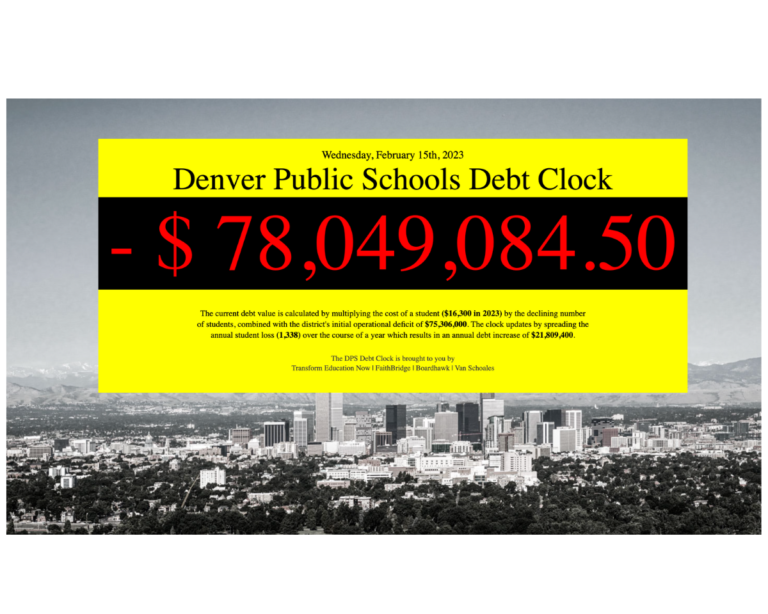

The simple, straightforward Denver Public Schools Debt Clock website, debuting today, serves as a stark reminder that postponing important decisions for political reasons can be costly -– literally as well as figuratively.

With Denver Public Schools innovation plan renewals coming up for votes over the next few months, we’ll be able to see in real time just how badly the school board has, with its meddling, damaged the concept of innovation.

Students, namely Black boys, are significantly more likely to graduate high school and enroll in college if they have a Black man as a teacher in elementary school. Black boys improve standardized test scores when they have Black men as teachers. Simply put, Black boys – and students more broadly – benefit from having Black men in the classroom.

Last week I came across the latest example of at least one Denver’s school board member focusing on the trivial in place of substance, while simultaneously trying to use board power to breathe down the neck of innovation schools.

We love and support our students, and we encourage their interests and needs.

As East High parents, we demand the school board resign. More than 1,600 others agree

The current Denver Public Schools Board of Education has failed in its oversight responsibilities and has demonstrated an inability to lead and manage effectively. We are among a group of DPS parents that has banded together and launched a petition drive to demand that all seven members resign immediately.